Understanding how to design pig waste systems is crucial for sustainable and responsible pig farming. Effective waste management not only protects the environment from harmful pollutants but also contributes significantly to the economic viability of pig production. This guide offers a detailed exploration of the essential elements needed to create efficient and environmentally sound pig waste systems.

From the initial site selection and waste characteristics analysis to the implementation of advanced treatment technologies and nutrient management strategies, this document will walk you through the key considerations. We’ll cover everything from collection and storage methods to regulatory compliance and economic aspects, providing a comprehensive overview for farmers, engineers, and anyone interested in this vital area of agriculture.

Introduction to Pig Waste Management

Effective pig waste management is crucial for sustainable pig farming. It encompasses the collection, storage, treatment, and utilization of manure produced by pigs. This process protects the environment, safeguards human health, and enhances the economic viability of pig production.Improper pig waste management leads to significant environmental and economic consequences. Runoff from manure storage can contaminate surface and groundwater, harming aquatic ecosystems and posing risks to human health through pathogens and nutrient overload.

Air pollution, resulting from the release of ammonia, hydrogen sulfide, and greenhouse gases (GHGs) such as methane and nitrous oxide, contributes to respiratory problems, acid rain, and climate change. Economically, poor management can result in increased costs for waste disposal, reduced land values, and potential fines or legal liabilities.

Core Goals of a Well-Designed Pig Waste System

The primary goals of a well-designed pig waste system are multifaceted, encompassing environmental protection, resource conservation, and economic sustainability. The following points detail these objectives.

- Protecting Water Quality: This involves preventing the contamination of surface and groundwater sources by manure runoff and leachate. Systems should incorporate measures such as impervious storage facilities, proper siting to avoid floodplains, and effective land application practices. For example, a study by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) found that improperly managed swine operations were a significant source of nutrient pollution in the Chesapeake Bay watershed, highlighting the importance of water quality protection.

- Minimizing Air Emissions: Controlling the release of harmful gases, particularly ammonia, hydrogen sulfide, and GHGs, is essential. This can be achieved through various technologies, including covered manure storage, anaerobic digestion, and biofilters. Research published in the journal Environmental Science & Technology demonstrated that anaerobic digestion of pig manure could reduce methane emissions by up to 90% compared to open lagoons.

- Reducing Odor Nuisance: Minimizing offensive odors is important for maintaining good relationships with neighboring communities and ensuring a positive public perception of pig farming. This can be accomplished through odor control technologies like biofilters, manure aeration, and frequent manure removal from housing facilities.

- Recovering and Utilizing Nutrients: Maximizing the value of manure as a fertilizer and source of renewable energy is key. This involves nutrient management planning to ensure proper land application rates, and technologies like anaerobic digestion to produce biogas for electricity generation. A report by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) estimated that the nutrient content of pig manure, if properly utilized, could significantly reduce the need for synthetic fertilizers, leading to both economic and environmental benefits.

- Protecting Soil Health: Implementing practices that avoid soil compaction and nutrient imbalances. It involves adopting land application strategies that match nutrient application to crop needs, reducing the risk of soil degradation and promoting long-term soil fertility.

- Ensuring Economic Viability: Designing systems that are cost-effective to operate and maintain, while also providing opportunities for revenue generation through the sale of biogas, compost, or other byproducts. An economic analysis conducted by Iowa State University showed that the implementation of anaerobic digestion systems could result in significant cost savings for pig farmers over the long term, by reducing energy expenses and providing additional income streams.

Understanding Waste Characteristics

To effectively design pig waste systems, a thorough understanding of the waste’s characteristics is essential. This knowledge informs the selection of appropriate treatment technologies and ensures compliance with environmental regulations. Pig waste, a complex mixture, varies significantly based on several factors, influencing the design and performance of waste management systems.

Primary Components of Pig Waste and Their Properties

Pig waste primarily consists of feces, urine, spilled feed, and water used for cleaning. Understanding the properties of these components is fundamental to waste management.The main components include:

- Feces: Primarily composed of undigested feed, bacteria, and sloughed-off intestinal cells. Feces contribute significantly to the solid content and contain organic matter, including carbohydrates, proteins, and fats. They are a major source of odors and pathogens.

- Urine: Contains water, urea, creatinine, minerals, and trace amounts of other substances. Urine is a significant source of nitrogen and phosphorus, which can contribute to water pollution through eutrophication.

- Spilled Feed: Represents a portion of the feed that pigs do not consume, leading to increased solid content and biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) in the waste.

- Wash Water: Used for cleaning the pig pens and contributes to the overall waste volume. The amount of wash water used can significantly influence the waste’s dilution and the concentrations of pollutants.

Factors Influencing Waste Volume and Composition

Several factors influence the volume and composition of pig waste. These factors must be considered when designing waste management systems to ensure optimal performance.

- Pig Age: The volume and composition of waste vary with the pig’s age. Young pigs produce less waste with a different composition compared to finishing pigs. The waste from younger pigs tends to have a higher percentage of solids due to less efficient digestion.

- Diet: The type and amount of feed influence waste characteristics. Diets high in fiber increase the solid content of the waste. Diets with high protein content increase nitrogen levels.

- Housing: Housing systems (e.g., slatted floors, solid floors, deep-pit systems) affect waste collection and characteristics. Slatted floor systems often result in more dilute waste, while solid floor systems may produce more concentrated waste.

- Water Consumption: Water intake is directly related to waste volume. Increased water consumption, often influenced by temperature and diet, dilutes the waste.

- Health Status: Illness can alter waste composition. For instance, diarrhea can increase water content and change the solid fraction.

Typical Waste Characteristics

The following table summarizes typical waste characteristics for pig manure. These values are approximate and can vary based on the factors discussed above. The values are presented as ranges to reflect this variability. The table provides data on solids, BOD, nitrogen, and phosphorus. The data presented below is for illustration purposes and sourced from common agricultural engineering references.

It is crucial to analyze the waste produced by specific farms for accurate system design.

| Parameter | Units | Typical Range | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Solids | % | 2 – 15 | Varies with diet, age, and housing system. |

| Biochemical Oxygen Demand (BOD) | mg/L | 5,000 – 30,000 | Indicates the amount of oxygen needed to break down organic matter. |

| Total Nitrogen | mg/L | 500 – 4,000 | Includes organic and inorganic forms (e.g., ammonia). |

| Total Phosphorus | mg/L | 100 – 800 | Essential nutrient that can contribute to water pollution. |

Site Selection and Planning

Selecting the right site is paramount for the success and sustainability of any piggery and its associated waste management system. Poor site selection can lead to a multitude of problems, including environmental pollution, regulatory violations, and operational inefficiencies. Careful planning during this stage minimizes risks and maximizes the long-term viability of the operation.

Crucial Considerations for Site Selection

Several key factors must be carefully evaluated when choosing a location for a piggery and its waste management infrastructure. These factors influence the environmental impact, operational costs, and regulatory compliance of the facility. Ignoring these considerations can lead to significant financial and legal repercussions.

- Soil Type and Drainage: The soil’s characteristics are crucial for waste management. Impermeable soils (like clay) are generally preferred for lagoons and waste storage areas to prevent groundwater contamination. Soil testing should be conducted to determine the soil’s permeability, water-holding capacity, and suitability for various waste treatment methods. Good drainage is essential to prevent waterlogging and the accumulation of surface runoff.

- Water Availability: An adequate and reliable water supply is essential for pig production, cleaning, and waste management. Consider the source, quantity, and quality of the water available. Assess the potential impact of the piggery on existing water resources and ensure compliance with water usage regulations. The amount of water required varies depending on the production system and pig size. For instance, a finishing pig may consume between 10 to 20 liters of water per day.

- Proximity to Neighbors and Sensitive Areas: The location should minimize potential nuisances, such as odor and noise, to neighboring residents. Buffer zones, natural barriers (trees, hills), and prevailing wind patterns should be considered. The proximity to sensitive areas like schools, hospitals, and residential areas is crucial to avoid potential conflicts and ensure social acceptance of the operation.

- Topography and Elevation: The site’s topography impacts drainage, waste management system design, and construction costs. A gently sloping site is often ideal for efficient drainage and gravity-fed waste systems. The elevation should be considered in relation to floodplains and potential flood risks.

- Prevailing Wind Direction: Understanding the prevailing wind patterns is critical for minimizing odor issues. Locate the piggery and waste treatment facilities downwind from sensitive receptors (e.g., residences). Windbreaks, such as strategically planted trees, can also help mitigate odor transport.

- Transportation Access: Consider the accessibility of the site for feed delivery, pig transport, and waste removal. Proximity to major roads and highways reduces transportation costs. Evaluate the road infrastructure’s capacity to handle heavy vehicle traffic.

- Regulatory Requirements and Zoning: Thoroughly research and comply with all local, regional, and national regulations related to pig production, waste management, and environmental protection. This includes zoning regulations, permits for construction and operation, and environmental impact assessments. Failure to comply can result in fines, legal action, and operational shutdowns.

Checklist for Assessing Site Suitability

A comprehensive checklist ensures that all critical factors are considered during site selection. This systematic approach minimizes the risk of overlooking crucial aspects. This checklist should be completed for each potential site.

- Soil Assessment:

- Soil type and permeability testing results

- Soil drainage characteristics

- Presence of groundwater and its depth

- Water Availability:

- Water source (well, municipal supply, etc.)

- Water quantity and quality testing results

- Water rights and permits

- Proximity Assessment:

- Distance to nearest residences and sensitive areas

- Prevailing wind direction and wind rose data

- Buffer zone requirements

- Environmental Considerations:

- Proximity to surface water bodies (rivers, lakes)

- Floodplain designation and flood risk assessment

- Presence of wetlands or protected areas

- Regulatory Compliance:

- Zoning regulations and permitted land uses

- Permitting requirements for construction and operation

- Environmental impact assessment requirements

- Operational Factors:

- Accessibility for transportation (roads, feed delivery, pig transport)

- Topography and slope of the land

- Availability of utilities (electricity, water)

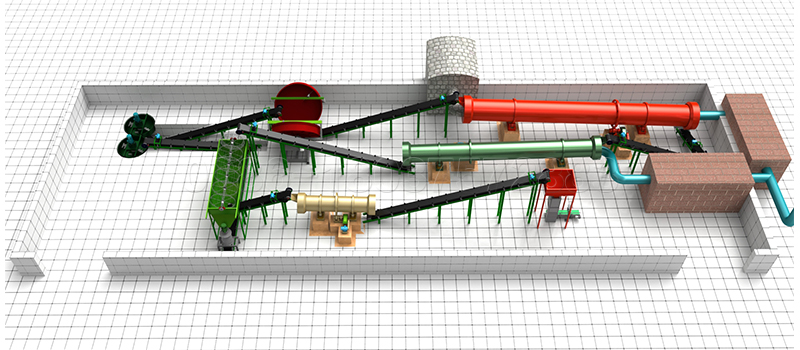

Diagram of a Typical Piggery and Waste Management Components

The following diagram illustrates a typical layout of a piggery and its associated waste management components. This schematic provides a visual representation of the spatial relationships between different elements of the operation. Note that the specific design will vary based on the size of the operation, the waste treatment method employed, and local regulations.

Diagram Description: The diagram illustrates a simplified layout of a piggery and its waste management system.

It depicts a rectangular pig housing structure with multiple pens. Outside the housing, a series of waste management components are illustrated.

Key Components and Their Arrangement:

1. Pig Housing

Rectangular structure divided into pens. Pens are where the pigs are housed.

2. Waste Collection System

A system for collecting manure and wastewater from the pig housing. This could include a gutter system, flush system, or other methods.

3. Manure Storage

A designated area for storing solid manure. This may be a covered building or an open-air storage area.

4. Wastewater Treatment Lagoon (Anaerobic Lagoon)

A large, lined pond where wastewater is treated anaerobically. This lagoon is located away from the pig housing and is designed to reduce the organic load in the wastewater.

5. Solids Separation

A system for separating solids from the wastewater. This might include a settling basin or a mechanical separator.

6. Land Application Area

The area where treated wastewater or manure is applied to the land, usually for crop fertilization. The area is often located away from sensitive areas.

7. Access Roads

Roads providing access to the piggery and waste management components for vehicles.

8. Buffer Zone

A designated area surrounding the piggery, providing a separation from neighboring properties and sensitive areas. It is often planted with trees or other vegetation to act as a visual and odor barrier.

9. Monitoring Wells

Wells strategically placed to monitor groundwater quality and detect any potential contamination.

Flow of Waste:

The diagram illustrates the flow of waste starting from the pig housing, moving through the collection system, potentially through solids separation, to the lagoon for treatment, and finally to the land application area for beneficial use. The solid manure storage area receives manure that is collected separately.

Waste Collection and Storage Methods

Efficient waste collection and storage are crucial components of a successful pig waste management system. The chosen methods significantly impact environmental sustainability, operational costs, and the potential for resource recovery. This section explores various collection and storage techniques, analyzing their advantages, disadvantages, and relative cost-effectiveness.

Waste Collection Methods

Various methods exist for collecting pig waste, each with its own operational characteristics and suitability depending on farm size, layout, and environmental regulations. Selecting the most appropriate method is essential for minimizing environmental impact and optimizing waste management efficiency.

- Flush Systems: Flush systems utilize water to transport manure from the pig housing to a storage facility. These systems typically involve automated flushing cycles, often using recycled water.

- Advantages: They efficiently remove manure, reducing odor and fly problems within the housing. They can be easily automated, reducing labor requirements.

- Disadvantages: Flush systems generate large volumes of wastewater, requiring significant water resources and potentially increasing the risk of water pollution if not managed correctly. They also need regular maintenance to avoid clogging.

- Pit Storage: Pit storage systems involve the direct accumulation of manure within a pit beneath the pig housing. These pits are emptied periodically, usually annually or semi-annually.

- Advantages: They are relatively simple to operate and require less water compared to flush systems. They can also provide some anaerobic digestion, reducing odor and pathogen levels.

- Disadvantages: They can lead to higher concentrations of greenhouse gases (GHGs) if not properly managed. The infrequent emptying can lead to odor releases during agitation and emptying.

- Scrape Systems: Scrape systems use mechanical scrapers to collect manure from the housing floors and transport it to a storage facility. These systems are typically used in conjunction with solid-liquid separation.

- Advantages: They produce a drier manure fraction, which can be easier to handle and transport. They can also reduce odor emissions compared to some other systems.

- Disadvantages: They require regular maintenance and can be labor-intensive, depending on the level of automation. They may not be suitable for all housing designs.

Storage Options Comparison

Selecting the right storage option depends on factors like farm size, budget, and environmental regulations. Storage methods vary in their effectiveness and cost-effectiveness.

| Storage Option | Effectiveness | Cost-Effectiveness | Additional Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lagoon | Excellent for reducing odor and pathogen levels through anaerobic decomposition. Can be highly effective in reducing nitrogen concentrations, especially if managed properly. | Moderate initial cost, but can be cost-effective over the long term due to low operating costs. Requires proper siting and management to prevent environmental problems. | Commonly used in areas with warm climates. Regular monitoring of water quality is essential. Requires significant land area. The effectiveness of the lagoon system is strongly influenced by factors such as temperature, retention time, and organic loading rate. |

| Anaerobic Digester | Excellent for reducing odor and producing biogas (renewable energy). Can significantly reduce the volume of manure. It can also eliminate pathogens. | High initial investment costs, but can be economically viable with the sale of biogas or renewable energy credits. Operating costs can be high due to maintenance requirements. | Requires careful management of the anaerobic digestion process. The digestate can be used as fertilizer. The design and operational aspects of anaerobic digestion systems can vary significantly based on the specific feedstock, operating temperature, and reactor configuration. |

| Composting | Effective for reducing volume, stabilizing organic matter, and producing a valuable soil amendment. It eliminates pathogens and reduces odor if done correctly. | Moderate initial costs, relatively low operating costs. Requires adequate space and proper composting techniques. | The composting process must be carefully managed to ensure adequate aeration, moisture, and temperature. Composting can be done in various forms such as windrows, static piles, or in-vessel systems. The quality of the compost can vary significantly depending on the composting method. |

Waste Treatment Technologies

Effective pig waste management extends beyond collection and storage; it necessitates the implementation of treatment technologies to reduce environmental impact and potentially recover valuable resources. These technologies are crucial for minimizing odor, pathogen levels, and nutrient loads in the waste, thus protecting water and air quality. Various treatment methods exist, each with its own operational principles, advantages, and limitations.

Common Biological Treatment Methods for Pig Waste

Biological treatment methods are widely employed in pig waste management due to their ability to break down organic matter using microorganisms. These methods often offer cost-effectiveness and the potential for resource recovery. Several common biological treatment methods are used.

- Anaerobic Digestion: This process involves the breakdown of organic matter in the absence of oxygen. It produces biogas, a renewable energy source composed primarily of methane and carbon dioxide. The digestate, the remaining solid and liquid material, can be used as a fertilizer.

- Aerobic Treatment: This method utilizes oxygen to break down organic waste. Aerobic processes can include activated sludge systems, aerated lagoons, and trickling filters. These systems typically result in a lower production of greenhouse gases compared to anaerobic digestion, but they require a significant energy input for aeration.

- Constructed Wetlands: These are engineered systems that mimic natural wetlands. They use plants, soil, and microorganisms to filter and treat wastewater. Constructed wetlands are particularly effective in removing nutrients and pathogens from pig waste effluent.

Operational Principles and Efficiency of Anaerobic Digesters

Anaerobic digesters are closed systems designed to facilitate the anaerobic digestion process. Their efficiency depends on several factors, including the feedstock composition, temperature, retention time, and the presence of inhibitory substances. The process typically involves four stages.

- Hydrolysis: Complex organic polymers (proteins, carbohydrates, lipids) are broken down into simpler molecules.

- Acidogenesis: The products of hydrolysis are converted into volatile fatty acids, alcohols, carbon dioxide, and hydrogen.

- Acetogenesis: The volatile fatty acids and alcohols are converted into acetic acid, hydrogen, and carbon dioxide.

- Methanogenesis: Methane and carbon dioxide are produced from acetic acid, hydrogen, and carbon dioxide.

The efficiency of an anaerobic digester is often measured by the amount of biogas produced and the reduction in organic matter (measured as Chemical Oxygen Demand or COD). Well-managed digesters can achieve COD removal efficiencies of 70-90% and produce significant amounts of biogas. For example, a pig farm with 1,000 pigs can potentially generate enough biogas to power a combined heat and power (CHP) unit, providing electricity and heat for the farm.

The digestate, after further treatment, can be used as a fertilizer, reducing the need for synthetic fertilizers and improving soil health.

Process Flow of a Constructed Wetland System for Pig Waste Treatment

Constructed wetlands offer a natural and sustainable approach to pig waste treatment. The process involves several stages, each contributing to the removal of pollutants.

Influent (Wastewater from piggery): Wastewater enters the wetland system.

Pre-treatment (Optional): Solids may be removed through a settling basin or screening.

Wetland Cells: Wastewater flows through a series of wetland cells, each planted with specific vegetation. These cells are often designed with different depths and media (gravel, sand) to enhance treatment.

Pollutant Removal Mechanisms:

- Physical Filtration: Solids are trapped by the media and plant roots.

- Biological Uptake: Plants and microorganisms absorb nutrients (nitrogen, phosphorus).

- Decomposition: Organic matter is broken down by microorganisms.

- Chemical Reactions: Chemical processes, such as nitrification and denitrification, occur in the soil and water.

Effluent (Treated Water): Treated water is discharged, meeting regulatory standards for discharge or reuse (e.g., irrigation).

Nutrient Management and Utilization

Effective nutrient management is crucial for sustainable pig farming. It involves recovering valuable nutrients from pig waste and utilizing them responsibly to minimize environmental impact and maximize resource efficiency. This approach reduces the reliance on synthetic fertilizers, protects water quality, and contributes to a circular economy within the agricultural sector.

Importance of Nutrient Recovery

Pig waste contains significant amounts of essential plant nutrients, primarily nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and potassium (K). Recovering these nutrients is vital for several reasons:

- Reducing Environmental Pollution: Improperly managed pig waste can lead to significant environmental problems. Runoff from manure storage or land application can contaminate surface and groundwater with nutrients, causing eutrophication (excessive algae growth) in water bodies. Nutrient recovery minimizes this risk.

- Conserving Resources: Recovering nutrients from waste reduces the need for mining phosphorus and producing nitrogen fertilizers, which are energy-intensive processes. This conserves finite resources and lowers the carbon footprint of agriculture.

- Economic Benefits: Utilizing recovered nutrients as fertilizer can significantly reduce the cost of commercial fertilizers for farmers. Furthermore, some nutrient recovery technologies can generate additional revenue streams, such as biogas production from anaerobic digestion.

- Improving Soil Health: Properly managed pig waste can improve soil health by adding organic matter and enhancing its water-holding capacity and nutrient retention. This promotes sustainable agricultural practices.

Utilizing Treated Waste as Fertilizer

Treated pig waste can be effectively utilized as a fertilizer source, providing essential nutrients for crop production. The specific application methods and rates depend on the treatment process, the nutrient content of the treated waste, and the crop’s nutrient requirements.

Here are some examples of how treated pig waste can be used as fertilizer:

- Liquid Manure Application: Anaerobically digested effluent (liquid manure) can be applied to croplands using various methods, such as irrigation or injection. This method is suitable for crops with high nitrogen demands, like corn or wheat. Application rates should be based on soil testing and the crop’s nutrient needs to avoid over-application and potential environmental impacts.

- Solid Manure Application: Composted or dewatered solids from pig waste can be applied to fields as a solid fertilizer. This form is easier to handle and transport than liquid manure. It provides a slow-release source of nutrients and improves soil structure.

- Nutrient-Rich Effluent for Irrigation: Treated effluent can be used for irrigation. This is particularly effective in areas with water scarcity, as it provides both water and nutrients to crops. This approach needs careful management to prevent salt buildup in the soil.

- Production of Struvite: Struvite is a slow-release fertilizer produced by precipitating magnesium ammonium phosphate from wastewater. It contains phosphorus and nitrogen, both essential nutrients for plant growth. This method is gaining popularity as a way to recover phosphorus from wastewater streams.

Environmental Benefits of Recycling Nutrients

Recycling nutrients from pig waste offers significant environmental benefits, contributing to a more sustainable and eco-friendly agricultural system.

These are the main environmental benefits:

- Reduced Water Pollution: By recovering nutrients and preventing their release into the environment, the risk of water pollution from runoff and leaching is significantly reduced. This protects aquatic ecosystems and ensures clean water resources.

- Reduced Greenhouse Gas Emissions: Nutrient recovery technologies, such as anaerobic digestion, can reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Anaerobic digestion produces biogas (primarily methane), which can be used as a renewable energy source, reducing reliance on fossil fuels.

- Reduced Reliance on Synthetic Fertilizers: Utilizing recovered nutrients as fertilizer reduces the demand for synthetic fertilizers, which require significant energy for production and can contribute to greenhouse gas emissions.

- Improved Soil Health: Applying treated waste to the soil as fertilizer enhances soil health by increasing organic matter content, improving water retention, and enhancing nutrient availability.

- Conservation of Phosphorus Resources: Phosphorus is a finite resource. Recovering phosphorus from pig waste reduces the need for mining phosphate rock, preserving this valuable resource for future generations.

System Design Considerations

Designing a pig waste system requires careful planning and consideration of various factors to ensure its efficiency, environmental sustainability, and compliance with regulations. This section Artikels the key steps involved in the design process, emphasizing the importance of regulatory compliance and the factors influencing system sizing.

Flow Chart of Pig Waste System Design

The design process for a pig waste system is best understood through a structured approach. The following flowchart illustrates the key steps involved:A flowchart illustrating the pig waste system design process:

1. Assessment and Planning

Gather information on farm size, pig population, and production cycle.

Analyze existing waste management practices.

Determine site characteristics (soil type, topography, proximity to water bodies, etc.).

Identify local regulations and permit requirements.

2. Waste Characterization

Analyze waste composition (solids, liquids, nutrients, pathogens).

Estimate waste generation rates.

Determine waste characteristics that impact treatment and storage.

3. Technology Selection

Evaluate available waste treatment technologies (e.g., anaerobic digestion, composting, constructed wetlands).

Consider factors such as cost, efficiency, and environmental impact.

Select the most appropriate technology or combination of technologies.

4. System Design

Design waste collection and storage systems.

Design treatment processes based on selected technologies.

Design nutrient management and utilization strategies.

Consider odor control measures.

5. Permitting and Regulatory Compliance

Prepare permit applications.

Ensure the design meets all applicable environmental regulations.

6. Construction and Implementation

Oversee construction of the system.

Implement the chosen waste management practices.

7. Operation and Maintenance

Develop an operation and maintenance plan.

Monitor system performance.

Adjust management practices as needed.

8. Monitoring and Evaluation

Regularly monitor the system’s effectiveness.

Evaluate the environmental impact.

Make adjustments to optimize performance and compliance.

Regulatory Compliance in System Design

Regulatory compliance is a critical aspect of pig waste system design, ensuring environmental protection and public health. Failure to comply can result in significant penalties, including fines, legal action, and the suspension of farm operations. Adherence to regulations minimizes the risk of environmental damage and contributes to the long-term sustainability of the pig farming operation.The importance of regulatory compliance is reflected in several key areas:* Environmental Protection: Regulations aim to prevent pollution of water resources (surface and groundwater) and protect air quality by controlling emissions.

Public Health

Regulations address potential risks to public health from pathogens, odors, and vectors associated with pig waste.

Permitting Requirements

Compliance with permit requirements is essential for legal operation. This involves submitting detailed plans, obtaining necessary approvals, and adhering to specific operational standards.

Nutrient Management

Regulations often dictate the amount of nutrients (nitrogen and phosphorus) that can be applied to land, impacting the design of nutrient management plans.

Waste Disposal

Regulations specify approved methods for waste disposal, such as land application, composting, or other approved treatment technologies.

Record Keeping and Reporting

Maintaining accurate records of waste generation, treatment, and disposal is a common regulatory requirement.For example, in the United States, the Clean Water Act and the Clean Air Act, along with state-specific regulations, govern pig waste management. In the European Union, the Nitrates Directive and the Industrial Emissions Directive set standards for manure management and emissions.

Key Factors Influencing System Size and Capacity

The size and capacity of a pig waste system are determined by several factors that directly influence its effectiveness and cost-efficiency. Understanding these factors is essential for designing a system that adequately handles the volume and characteristics of the waste generated.Key factors to consider:* Pig Population: The number of pigs housed on the farm is the primary driver of waste generation.

System capacity must be sufficient to handle the waste produced by the entire herd.

Pig Production Stage

Different stages of pig production (e.g., farrowing, growing, finishing) generate different volumes and characteristics of waste. The system design must accommodate these variations.

Waste Generation Rates

Waste generation rates vary depending on pig age, diet, and environmental conditions. These rates are typically expressed in terms of volume or weight of waste produced per pig per day.

Manure Collection and Handling Methods

The chosen methods for collecting and handling manure (e.g., flush systems, scraping systems) influence the volume and characteristics of the waste.

Waste Storage Duration

The length of time manure is stored before treatment or land application impacts the required storage capacity. Regulations often dictate minimum storage periods.

Treatment Technology

The chosen treatment technology influences the size and capacity of the system. Some technologies require larger treatment units than others.

Nutrient Management Plan

The nutrient management plan determines the amount of manure that can be applied to land, which affects the storage and treatment requirements.

Land Availability

The availability of land for waste application and the capacity of the land to receive nutrients limit the amount of manure that can be utilized.

Climate

Climatic conditions (e.g., rainfall, temperature) affect waste generation, storage, and treatment.

Regulatory Requirements

Local, regional, and national regulations impact the size and capacity of the system through restrictions on storage, treatment, and land application.For example, a farm with 1,000 finishing pigs may generate approximately 10,000 gallons of manure per week. This estimate, along with storage requirements (e.g., six months of storage), would influence the sizing of storage lagoons or other storage facilities.

Similarly, the selection of an anaerobic digester would depend on the volume and characteristics of the manure, as well as the desired biogas production capacity.

Odor Control Strategies

Managing odor is a critical aspect of pig waste system design, impacting both the environment and the surrounding community. Odor emissions from pig waste can lead to nuisance complaints, health concerns, and reduced property values. Effective odor control strategies are therefore essential for sustainable and socially responsible pig farming operations.

Primary Sources of Odor in Pig Waste Systems

The primary sources of odor in pig waste systems are complex and interconnected, originating from various stages of waste management. Understanding these sources is crucial for implementing targeted control measures.* Manure Production: Odor compounds are generated directly in the manure due to the breakdown of organic matter by anaerobic bacteria.

Waste Collection and Storage

Slurry tanks, lagoons, and storage facilities are significant sources of odor as they provide an environment conducive to anaerobic decomposition.

Waste Treatment

During treatment processes, such as anaerobic digestion or composting, odor can be released if not properly managed.

Land Application

Applying manure to land, whether through surface spreading or injection, can release significant amounts of odor, particularly in the days following application.

Feed and Animal Management

The type of feed, animal health, and housing conditions can influence the composition of manure and, consequently, the intensity of odor emissions.

Odor Control Techniques

A variety of techniques can be employed to control odor emissions from pig waste systems, each with its own advantages and limitations.* Biofilters: Biofilters use a bed of organic material, such as wood chips or compost, to filter air containing odor-causing compounds. The microorganisms in the filter break down the compounds, reducing odor emissions.

Operation

Odorous air is forced through the biofilter media. The microorganisms, typically bacteria, fungi, and other organisms, consume the volatile organic compounds (VOCs) that cause the odor.

Maintenance

Requires regular monitoring of moisture content, pH, and pressure drop across the filter bed. The media needs periodic replacement as it degrades and loses its effectiveness.

Effectiveness

Highly effective for removing a wide range of odor compounds, especially hydrogen sulfide and ammonia.

Example

A study in the Netherlands showed that biofilters can reduce odor emissions from pig houses by up to 90%.* Covers: Covering manure storage facilities, such as lagoons and tanks, can significantly reduce odor emissions by preventing the release of volatile compounds into the atmosphere.

Types

Covers can be made from various materials, including geomembranes, floating covers, or solid covers.

Operation

Covers physically separate the manure from the air, reducing the surface area available for odor release.

Effectiveness

Effective at reducing odor emissions, particularly from lagoons and storage tanks. The effectiveness depends on the type and design of the cover.

Example

Floating covers on anaerobic lagoons can reduce odor emissions by 70-90% compared to uncovered lagoons.* Chemical Treatments: Chemical treatments involve adding substances to the manure or air to reduce odor emissions.

Types

These include additives that inhibit microbial activity, absorb odor compounds, or mask odors. Common examples are iron salts, enzymes, and odor masking agents.

Operation

Chemical treatments can be applied directly to the manure, sprayed into the air, or incorporated into the feed.

Effectiveness

Effectiveness varies depending on the chemical used, the application method, and the specific odor compounds present. Some chemicals can be highly effective in specific situations.

Example

Adding iron chloride to manure can reduce hydrogen sulfide emissions, which is a major contributor to odor.* Aeration: Aeration involves introducing oxygen into the manure to promote aerobic decomposition, which produces less odor than anaerobic decomposition.

Types

Aeration can be achieved through mechanical aerators, diffused air systems, or other methods.

Operation

Oxygen is supplied to the manure, which encourages the growth of aerobic microorganisms that break down organic matter.

Effectiveness

Effective at reducing odor emissions, especially hydrogen sulfide and other sulfur-containing compounds.

Example

Aerating a lagoon can reduce odor emissions by 50-70% compared to an unaerated lagoon.* Dietary Manipulation: Adjusting the pig’s diet can reduce the amount of odor-producing compounds in the manure.

Types

This can involve reducing the protein content of the feed, adding fiber, or using feed additives that improve nutrient digestibility.

Operation

By optimizing the diet, less undigested protein and other nutrients are excreted in the manure, which reduces the amount of odor-producing compounds.

Effectiveness

Can reduce odor emissions, particularly ammonia and volatile fatty acids.

Example

Feeding pigs a diet with reduced crude protein can reduce ammonia emissions by up to 20%.

Comparison of Odor Control Methods

The following table provides a comparison of different odor control methods, including their effectiveness and associated costs.

| Odor Control Method | Effectiveness | Cost | Maintenance Requirements | Additional Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biofilters | High (for specific compounds) | Moderate to High (initial investment and media replacement) | High (monitoring, media replacement) | Requires specific environmental conditions (moisture, pH), may freeze in cold climates. |

| Covers | High (depending on cover type) | Moderate to High (initial investment) | Moderate (repair, maintenance) | Can also control gas emissions (methane, ammonia), may require specialized installation. |

| Chemical Treatments | Variable (depending on chemical and application) | Low to Moderate (ongoing costs) | Low to Moderate (application, monitoring) | May require regulatory approval, potential environmental impacts. |

| Aeration | Moderate to High | Moderate to High (energy consumption, equipment costs) | Moderate (equipment maintenance) | Can improve wastewater quality, requires careful design to avoid excessive energy use. |

| Dietary Manipulation | Moderate | Low to Moderate (feed costs) | Low (monitoring feed composition) | Requires careful diet formulation, may affect pig performance. |

Solids Separation Techniques

Solids separation is a critical process in pig waste management, aiming to remove solid particles from the liquid waste stream. This process offers several benefits, including reducing the volume of waste for treatment and storage, facilitating nutrient recovery, and improving the efficiency of subsequent treatment technologies. Various techniques are employed to achieve solids separation, each with its own advantages and disadvantages depending on the specific characteristics of the waste and the desired outcomes.

Methods for Separating Solids from Liquid Pig Waste

Several methods are used to separate solids from liquid pig waste, each based on different physical principles. The choice of method depends on factors like the size and concentration of solids, the desired degree of separation, and the overall cost-effectiveness of the system.

- Sedimentation: This is a simple and widely used method that relies on gravity to settle solid particles. Waste is held in a large tank, allowing solids to settle to the bottom, forming sludge, while the clarified liquid is decanted from the top. Sedimentation is most effective for removing larger particles.

- Screening: Screening involves passing the waste through a screen or filter to remove solid particles based on size. Screens can range from coarse screens for removing large debris to fine screens for removing smaller particles. Screening is often used as a pre-treatment step to protect downstream equipment.

- Centrifugation: Centrifugation uses centrifugal force to separate solids from liquids. The waste is spun at high speeds in a centrifuge, forcing the denser solids to the outside, where they are collected. Centrifugation can effectively separate very fine particles and is often used to produce a drier solid fraction.

- Filtration: Filtration involves passing the waste through a filter medium, such as a cloth or membrane, to remove solids. Different types of filters, such as belt filters or membrane filters, can be used depending on the desired level of separation. Filtration is generally used to remove very fine solids.

Applications of Separated Solids

The separated solids, often referred to as sludge or manure solids, can be utilized in several ways. The specific application depends on the characteristics of the solids, the regulations in place, and the economic feasibility of the options.

- Composting: Composting is a biological process that converts organic solids into a stable, humus-like material. The separated solids are mixed with bulking agents, such as wood chips or straw, and allowed to decompose under controlled conditions. Composting reduces the volume of solids, eliminates pathogens, and produces a valuable soil amendment. The composting process can take several weeks or months, depending on the composting method.

- Land Application: Land application is a common method for utilizing separated solids as a fertilizer. The solids are applied to agricultural land, providing nutrients to crops. The application rate must be carefully managed to avoid nutrient runoff and groundwater contamination. Nutrient management plans are essential for land application to ensure environmental protection.

- Anaerobic Digestion: Separated solids can be fed into an anaerobic digester to produce biogas, a renewable energy source. The anaerobic digestion process breaks down organic matter in the absence of oxygen, producing methane and other gases. The digested solids, known as digestate, can then be used as a fertilizer.

- Other Uses: Separated solids can also be used for other purposes, such as animal bedding, production of construction materials, or production of biofuels. The feasibility of these options depends on the characteristics of the solids and the availability of suitable processing technologies.

Detailed Description of Solid Separation Using Sedimentation

Sedimentation is a fundamental solids separation technique that utilizes the principle of gravity to separate solid particles from liquid waste. This process is relatively simple, cost-effective, and commonly used in pig waste management systems.

Process Overview:

The sedimentation process typically involves the following steps:

- Influent Waste Introduction: The liquid pig waste is introduced into a sedimentation tank. The tank is designed to provide sufficient retention time for solids to settle.

- Settling: As the waste enters the tank, the solid particles, which are denser than the liquid, begin to settle to the bottom due to gravity. The settling rate depends on the particle size, density, and the viscosity of the liquid.

- Sludge Accumulation: The settled solids accumulate at the bottom of the tank, forming a sludge layer. The sludge layer volume increases over time.

- Clarified Effluent Discharge: The clarified liquid, which is relatively free of solids, is decanted from the top of the tank. This effluent can then be further treated or stored.

- Sludge Removal: The accumulated sludge is periodically removed from the bottom of the tank. This can be done manually or mechanically using pumps or scrapers. The sludge is then transferred to a storage or treatment facility.

Tank Design Considerations:

The design of the sedimentation tank is crucial for efficient solids separation. Key design parameters include:

- Tank Volume: The tank volume is determined by the flow rate of the waste and the desired retention time, which is typically several hours.

- Tank Shape: Rectangular or circular tanks are commonly used. The shape affects the flow pattern within the tank and the efficiency of solids settling.

- Depth: The tank depth affects the settling distance for the solids. Deeper tanks can accommodate larger volumes of sludge.

- Inlet and Outlet Design: The inlet and outlet structures should be designed to minimize turbulence and ensure even flow distribution within the tank.

- Sludge Removal System: The sludge removal system should be designed to efficiently remove the accumulated sludge without disrupting the settling process.

Example:

Consider a pig farm with 1,000 sows producing approximately 10,000 gallons of waste per day. A sedimentation tank might be designed with a volume of 50,000 gallons, providing a 5-day retention time. The tank could be rectangular, with dimensions of 20 feet wide, 50 feet long, and 10 feet deep. The clarified effluent would be discharged to a storage lagoon, while the sludge would be removed periodically and composted.

This setup is common in areas with moderate to large-scale pig farming operations.

Water Quality Monitoring and Management

Effective water quality monitoring and management are crucial components of sustainable pig waste management systems. These practices ensure the protection of both human health and the environment by preventing pollution of water resources. Regular monitoring and appropriate management strategies help to minimize the negative impacts of pig farming on surrounding ecosystems.

Parameters to Monitor in Treated Wastewater

Monitoring the quality of treated wastewater is essential to assess the effectiveness of the waste treatment system and ensure compliance with environmental regulations. Several key parameters must be regularly monitored to evaluate the water quality.

- pH: The pH level indicates the acidity or alkalinity of the wastewater. It is important to maintain the pH within an acceptable range (typically 6.0 to 9.0) to protect aquatic life and ensure the effectiveness of disinfection processes.

- Biochemical Oxygen Demand (BOD): BOD measures the amount of oxygen consumed by microorganisms in the wastewater during the decomposition of organic matter. High BOD levels indicate a significant amount of organic pollution, which can deplete oxygen levels in receiving water bodies, harming aquatic life.

- Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD): COD measures the amount of oxygen required to chemically oxidize all organic and inorganic compounds in the wastewater. It provides a broader assessment of the organic load than BOD.

- Ammonia (NH₃-N): Ammonia is a nitrogenous compound that can be toxic to aquatic life, particularly at high concentrations. It is also a nutrient that can contribute to eutrophication, the excessive enrichment of water bodies with nutrients.

- Phosphorus (P): Phosphorus is another nutrient that can contribute to eutrophication. Elevated phosphorus levels in wastewater can lead to excessive algal growth, which can deplete oxygen levels and harm aquatic ecosystems.

- Total Suspended Solids (TSS): TSS measures the amount of solid material suspended in the wastewater. High TSS levels can cloud the water, reducing sunlight penetration and harming aquatic organisms.

- Total Nitrogen (TN): TN is the total amount of nitrogen present in the wastewater, including ammonia, nitrates, and nitrites. Monitoring TN is crucial for assessing the potential for nutrient pollution.

- Fecal Coliforms/E. coli: These bacteria are indicators of fecal contamination and the potential presence of pathogens. Monitoring fecal coliforms/E. coli is essential to protect human health if the treated wastewater is used for irrigation or other purposes.

Importance of Water Reuse and Conservation

Water reuse and conservation are critical aspects of sustainable pig waste management. Implementing these practices can significantly reduce the demand for freshwater resources and minimize the environmental impact of pig farming.

Water reuse involves utilizing treated wastewater for various purposes, such as irrigation, cleaning, and flushing. Water conservation encompasses implementing practices to reduce water consumption throughout the pig farming operation. By adopting these strategies, pig farmers can reduce their reliance on freshwater sources, lower operational costs, and contribute to environmental sustainability.

Water Quality Standards for Discharge and Reuse

Water quality standards for discharge and reuse vary depending on local regulations and the intended use of the treated wastewater. These standards are established to protect human health and the environment. The following table provides an example of typical water quality standards for discharge and reuse, but it is important to consult local regulations for specific requirements.

| Parameter | Discharge Standard (mg/L) | Reuse for Irrigation (mg/L) | Reuse for Livestock Watering (mg/L) |

|---|---|---|---|

| BOD | < 30 | < 50 | < 100 |

| TSS | < 30 | < 50 | < 100 |

| Ammonia-N | < 10 | < 5 | < 10 |

| Phosphorus | < 2 | < 5 | < 10 |

| Fecal Coliforms (CFU/100mL) | < 200 | < 1000 | < 1000 |

| pH | 6.0 – 9.0 | 6.0 – 9.0 | 6.0 – 9.0 |

Note: These are example values. Actual standards vary depending on the location and intended use of the water. Always consult local regulations.

Economic Aspects of Pig Waste Systems

Designing and implementing pig waste management systems involves significant financial considerations. Understanding the economic implications is crucial for making informed decisions about system selection, operation, and long-term sustainability. This section explores the various costs associated with these systems, potential economic benefits, and provides examples of return on investment (ROI) for different waste treatment technologies.

Costs Associated with Pig Waste Systems

The financial burden of pig waste systems encompasses a range of expenses, from initial investment to ongoing operational costs. A thorough analysis of these costs is vital for effective budgeting and financial planning.

- Design and Construction Costs: These are the upfront expenses incurred in setting up the system. They vary significantly depending on the technology chosen, the size of the piggery, and the site’s geographical characteristics. For example, a lagoon system typically has lower construction costs compared to a more sophisticated anaerobic digestion system.

- Equipment Costs: This includes the price of purchasing and installing necessary equipment such as pumps, mixers, separators, digesters, and aeration systems. The complexity and capacity of the equipment directly influence the overall cost.

- Labor Costs: Operating and maintaining a waste management system requires skilled labor. This includes personnel for monitoring, maintenance, and operation of the system. Labor costs can vary depending on the system’s complexity and the required level of expertise.

- Energy Costs: Many waste treatment technologies, such as aeration systems and anaerobic digesters, consume significant amounts of energy. Energy costs, which can fluctuate depending on the energy source (electricity, natural gas), represent a recurring operational expense.

- Maintenance Costs: Regular maintenance is essential to ensure the efficient and reliable operation of the waste management system. This includes the cost of spare parts, repairs, and scheduled servicing.

- Disposal Costs: If treated waste requires further disposal (e.g., land application of treated effluent or solids), there may be associated costs for transportation, permitting, and land rental.

- Permitting and Regulatory Costs: Complying with environmental regulations involves costs related to obtaining permits, conducting environmental monitoring, and reporting. These costs can vary depending on the specific regulations in the region.

Economic Benefits of Effective Waste Management

Investing in effective pig waste management can yield significant economic benefits, enhancing the profitability and sustainability of pig farming operations. Several examples of such benefits are provided.

- Fertilizer Production: Treated pig waste can be utilized as a valuable fertilizer source. This reduces the need to purchase synthetic fertilizers, leading to cost savings. The nutrient content of the treated waste can be tailored to specific crop requirements, improving yields.

- Biogas Generation: Anaerobic digestion of pig waste produces biogas, primarily methane, which can be used to generate electricity or heat. This reduces reliance on external energy sources, decreasing energy costs. Excess biogas can also be sold, generating additional revenue. For example, a medium-sized pig farm with an anaerobic digester can potentially generate enough electricity to offset a significant portion of its energy needs, or even sell excess electricity back to the grid.

- Reduced Environmental Penalties: Effective waste management minimizes the risk of environmental pollution, such as water contamination and odor emissions. This reduces the likelihood of incurring fines and penalties from regulatory agencies.

- Improved Animal Health and Productivity: Proper waste management contributes to a cleaner and healthier environment for the pigs, which can improve animal health and productivity. Healthier pigs grow faster and require fewer medications, resulting in lower production costs.

- Sale of Separated Solids: Separated solids can be used as a soil amendment or sold to other agricultural operations, creating a revenue stream. This can reduce the volume of waste that needs to be treated or disposed of.

Return on Investment for Different Waste Treatment Technologies

The ROI for different waste treatment technologies varies based on several factors, including the initial investment, operational costs, and revenue generation potential. The following table provides examples of potential ROI, noting that these are estimates and actual results will vary.

| Waste Treatment Technology | Initial Investment (USD) (Approximate) | Annual Operational Costs (USD) (Approximate) | Potential Revenue Streams | Estimated Payback Period (Years) (Approximate) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anaerobic Digestion | $100,000 – $1,000,000+ (depending on scale and complexity) | $10,000 – $50,000+ (labor, maintenance, energy) | Electricity generation (sale of electricity), heat generation, sale of digestate as fertilizer | 5 – 15 |

| Composting | $10,000 – $100,000 (depending on scale and equipment) | $1,000 – $10,000 (labor, turning equipment maintenance) | Sale of compost as soil amendment | 2 – 7 |

| Lagoon System | $5,000 – $50,000+ (depending on size and liner) | $500 – $5,000 (maintenance, monitoring) | Fertilizer value of effluent (land application) | 2 – 10 (depending on land value and fertilizer cost savings) |

| Solid Separation with Land Application | $5,000 – $50,000 (separator, storage) | $500 – $5,000 (maintenance, land application costs) | Fertilizer value of separated solids and effluent (land application) | 2 – 8 (depending on land value and fertilizer cost savings) |

Important Note: These are estimates and can vary widely. Detailed economic analysis, including site-specific conditions, market prices for energy and fertilizer, and regulatory requirements, is essential before making investment decisions.

Regulations and Permits

Managing pig waste effectively is not only crucial for environmental protection and public health, but also for legal compliance. Adhering to environmental regulations and obtaining necessary permits are essential steps in establishing and operating a sustainable pig waste management system. This section will delve into the regulatory landscape, permit requirements, and the application process, ensuring that your pig waste system aligns with environmental standards.

Key Environmental Regulations

Environmental regulations concerning pig waste management vary significantly depending on the region. The United States and the European Union, for example, have distinct regulatory frameworks. Understanding these differences is crucial for compliance.In the United States, the primary federal regulation is the Clean Water Act (CWA), enforced by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). The CWA regulates the discharge of pollutants into waters of the United States.

Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs), including many pig farms, are subject to National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permits under the CWA. States often have their own regulations that are at least as stringent as federal requirements. These state regulations might address issues like land application of manure, odor control, and setbacks from water bodies and residential areas. For instance, some states require nutrient management plans that dictate how manure is used as fertilizer to prevent nutrient runoff.In the European Union, the main regulatory framework includes the Industrial Emissions Directive (IED) and the Nitrates Directive.

The IED focuses on integrated pollution prevention and control, requiring operators to use Best Available Techniques (BAT) to minimize environmental impact. The Nitrates Directive aims to protect water quality by preventing nitrate pollution from agricultural sources. Member states implement these directives through national legislation, leading to variations in specific requirements. For example, some countries may have stricter limits on ammonia emissions or require specific waste treatment technologies.

Farmers are often required to develop and implement manure management plans, which must include details about manure storage, application, and nutrient balancing.

Permit Checklist for Operating a Pig Waste System

Obtaining the necessary permits is a critical step in establishing a pig waste system. The specific permits required depend on the size and type of operation, as well as the location. A typical checklist includes the following:* NPDES Permit (US) / Integrated Pollution Prevention and Control (IPPC) Permit (EU): Required for CAFOs in the US and larger pig farms in the EU. These permits regulate wastewater discharge and often include requirements for manure storage, treatment, and land application.

The permits Artikel monitoring and reporting requirements to ensure compliance.* Construction Permits: Necessary for building or modifying waste storage facilities, treatment systems, and other infrastructure. These permits ensure that the construction complies with local zoning laws and building codes.* Operating Permits: Required to operate the pig farm and waste management system. These permits are often issued by state or local environmental agencies and are renewed periodically.* Air Quality Permits: Required in some regions to regulate air emissions, including ammonia, hydrogen sulfide, and particulate matter.

These permits may necessitate the use of odor control technologies.* Land Application Permits: If manure is applied to land, permits may be required to ensure proper nutrient management and prevent runoff. These permits often involve developing and adhering to a nutrient management plan.* Stormwater Permits: Required if stormwater runoff from the farm could potentially impact water quality.* Waste Disposal Permits: Necessary for disposing of solid waste or other byproducts generated by the pig waste system.

Navigating the Permit Application Process

The permit application process can be complex, but it is manageable with careful planning and preparation. The following steps are typically involved:

1. Consult with Regulatory Agencies

Before starting the application process, it is advisable to contact the relevant environmental agencies (e.g., EPA in the US or local environmental protection agencies in the EU). Discuss the project, determine the specific permits required, and obtain application forms and guidance documents.

2. Develop a Comprehensive Plan

Prepare a detailed plan that Artikels the pig waste system, including the source of waste, collection methods, storage facilities, treatment technologies, and land application practices. This plan should demonstrate how the system will comply with all applicable regulations.

3. Conduct Environmental Assessments

Some permits may require environmental assessments to evaluate the potential impacts of the pig waste system on water quality, air quality, and other environmental factors.

4. Complete Application Forms

Fill out the permit application forms accurately and completely. Provide all required information, including engineering drawings, operational plans, and environmental impact assessments.

5. Submit the Application

Submit the completed application forms and supporting documentation to the appropriate regulatory agencies.

6. Public Notice and Review

The regulatory agencies will review the application and may issue a public notice, allowing stakeholders to comment on the proposed project.

7. Permit Issuance

If the application meets all requirements, the regulatory agency will issue the permit, which will include specific conditions and requirements that must be followed.

8. Ongoing Compliance

Once the permit is issued, it is essential to monitor and report on the system’s performance, as required by the permit. This includes regular sampling and analysis of wastewater, manure, and soil, as well as maintaining records of operations.

Example: A pig farm in Iowa, USA, operating under an NPDES permit, must regularly monitor and report the levels of nitrogen and phosphorus in its wastewater discharge. Failure to comply with these requirements can result in penalties, including fines or the suspension of the permit.

Conclusive Thoughts

In conclusion, designing effective pig waste systems is a multifaceted endeavor that demands careful planning, technological expertise, and a strong commitment to environmental stewardship. By integrating the principles Artikeld in this guide, pig farmers can not only minimize their environmental impact but also unlock valuable resources through nutrient recovery and waste-to-energy initiatives. This approach ensures a more sustainable and profitable future for pig farming while contributing to a healthier planet.