Managing farm waste is no longer just about disposal; it’s about sustainability, efficiency, and creating a circular economy on your farm. From the fields to the feedlots, agricultural operations generate diverse waste streams, each with unique challenges and opportunities. This guide will delve into the practical aspects of effective waste management, offering insights and strategies for farmers of all types and sizes.

We will explore various waste categories, from solid and liquid waste to gaseous emissions, examining their sources and environmental impacts. The discussion will then move to regulatory frameworks, waste reduction techniques, and specific management strategies for manure, liquid waste, and other farm byproducts. Furthermore, we’ll explore technologies, economic considerations, and health and safety protocols to ensure a holistic approach to farm waste management.

Understanding Farm Waste

Managing farm waste effectively is crucial for both environmental sustainability and the economic viability of agricultural operations. Understanding the types, sources, and environmental impacts of farm waste is the first step towards implementing sound waste management practices. This knowledge allows farmers to minimize waste generation, optimize resource utilization, and protect the environment from harmful pollutants.

Types of Farm Waste: Solid, Liquid, and Gaseous

Farm waste encompasses a variety of materials, broadly categorized into solid, liquid, and gaseous forms. Each type presents unique challenges and requires specific management strategies.

- Solid Waste: This category includes a wide array of materials, often bulky and potentially difficult to handle.

- Manure: This is a primary solid waste product, generated by livestock operations. Its composition varies based on animal species, diet, and bedding materials.

- Crop Residues: These include stalks, stems, leaves, and other plant materials left after harvesting. The amount and type of residue depend on the crop cultivated.

- Packaging Materials: Plastics, paper, cardboard, and other materials used for packaging fertilizers, pesticides, animal feed, and other farm inputs contribute significantly to solid waste.

- Dead Animals: Carcasses of livestock and poultry must be disposed of properly to prevent the spread of disease and odor.

- Plastic Film: This is frequently used for greenhouse coverings and mulching, and when it degrades it creates a waste stream that must be addressed.

- Liquid Waste: Liquid waste streams are also common on farms, often posing a significant risk of water contamination if not managed correctly.

- Manure Slurry: This is a mixture of manure and water, commonly found in livestock operations using liquid manure handling systems.

- Wash Water: Water used for cleaning animal housing, equipment, and processing facilities generates liquid waste.

- Pesticide and Herbicide Runoff: Improper application and handling of chemicals can lead to contaminated runoff.

- Silo Leachate: Liquid that drains from silage storage, containing organic matter and nutrients.

- Gaseous Waste: Gaseous emissions are often invisible but can significantly impact air quality and contribute to climate change.

- Ammonia (NH3): Released from manure, ammonia can cause respiratory problems in animals and humans and contribute to acid rain.

- Methane (CH4): A potent greenhouse gas produced during the anaerobic decomposition of organic matter, particularly in manure.

- Hydrogen Sulfide (H2S): This gas, also produced from manure, has a characteristic rotten egg smell and can be toxic at high concentrations.

- Greenhouse Gases: Carbon dioxide (CO2), nitrous oxide (N2O), and other gases released from various farm activities contribute to global warming.

Sources of Farm Waste by Agricultural Activity

Farm waste originates from various agricultural activities. Categorizing waste by its source helps identify specific areas where waste reduction and management strategies can be implemented.

- Livestock Operations: These operations are significant generators of manure, bedding materials, and dead animals. The size and type of livestock operation greatly influence the quantity and composition of waste.

- Dairy Farms: Produce large volumes of manure slurry and wash water.

- Poultry Farms: Generate significant amounts of manure, bedding, and dead birds.

- Swine Farms: Often use liquid manure handling systems.

- Beef Cattle Operations: Generate manure and may use bedding materials.

- Crop Production: Crop production generates crop residues, packaging materials, and pesticide/herbicide runoff. The type of crop and farming practices significantly impact the amount of waste produced.

- Harvesting Operations: Residues from harvesting activities, such as corn stover or wheat straw, contribute to waste.

- Fertilizer and Pesticide Use: Packaging waste and runoff from chemical applications are concerns.

- Irrigation: Runoff from irrigation systems can carry sediments and nutrients.

- Processing and Packing: Farms involved in processing or packing agricultural products generate additional waste, including food scraps, packaging, and wash water.

- Fruit and Vegetable Packing: Creates food waste and packaging waste.

- Grain Processing: Produces byproducts and packaging materials.

- Other Farm Activities: Various other activities contribute to farm waste.

- Building and Maintenance: Construction debris, used equipment, and other materials from farm maintenance contribute to waste.

- Fuel and Chemical Storage: Spills and leaks from fuel and chemical storage can contaminate soil and water.

Environmental Impact of Improper Farm Waste Disposal

Improper disposal of farm waste can have significant and far-reaching environmental consequences. Understanding these impacts underscores the importance of adopting responsible waste management practices.

- Water Pollution:

- Nutrient Runoff: Excess nutrients from manure, fertilizers, and crop residues can contaminate surface and groundwater, leading to eutrophication (excessive algae growth) in water bodies. This can deplete oxygen levels, harming aquatic life.

- Pesticide and Herbicide Contamination: Improper handling and disposal of these chemicals can pollute water sources, posing risks to human health and aquatic ecosystems.

- Pathogen Contamination: Manure can contain harmful bacteria and viruses that can contaminate water supplies, leading to human and animal illnesses.

- Air Pollution:

- Greenhouse Gas Emissions: Methane from manure and other sources contributes to climate change. Ammonia emissions can contribute to acid rain and respiratory problems.

- Odor and Particulate Matter: Waste can generate unpleasant odors and release particulate matter, impacting air quality and causing health issues.

- Soil Degradation:

- Soil Contamination: Improper disposal of chemicals, heavy metals, and other contaminants can pollute soil, affecting plant growth and posing risks to human and animal health.

- Soil Erosion: Poorly managed crop residues and exposed soil can increase erosion, leading to soil loss and water pollution.

- Habitat Destruction: Improper waste disposal can damage habitats and ecosystems, affecting biodiversity.

Regulatory Frameworks and Compliance

Understanding and adhering to regulatory frameworks is critical for responsible farm waste management. These regulations, which vary depending on location and type of farming operation, are designed to protect the environment and public health. Compliance not only ensures legal operation but also contributes to sustainable agricultural practices.

Relevant Regulations Governing Farm Waste Management

Farm waste management is subject to a complex web of regulations at local, regional, and national levels. These regulations aim to minimize environmental impact and ensure the safe handling and disposal of waste.

- Local Regulations: Local authorities, such as county or municipal governments, often have ordinances concerning waste disposal, composting, and manure management. These regulations may address issues like setbacks from water bodies, odor control, and permitted waste application rates. For example, a local ordinance might restrict manure spreading within a certain distance of residential areas or public waterways to prevent water contamination and reduce odor complaints.

- Regional Regulations: Regional agencies, such as state environmental protection agencies or regional water quality boards, establish broader regulations. These may include permitting requirements for large-scale animal feeding operations (CAFOs) or regulations regarding the application of fertilizers and pesticides. For instance, a regional agency might enforce nutrient management plans for farms located within a specific watershed to limit the amount of nitrogen and phosphorus entering local waterways.

- National Regulations: National environmental agencies, like the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in the United States, set overarching standards for waste management. These regulations may cover topics such as hazardous waste handling, wastewater discharge, and air quality. The EPA’s Clean Water Act, for example, regulates the discharge of pollutants into U.S. waters, including agricultural runoff.

Permitting Processes for Waste Disposal or Treatment

Farms often require permits for waste disposal or treatment activities, depending on the scale and nature of their operations. The permitting process ensures that waste management practices meet environmental standards.

- Permit Requirements: The need for a permit is usually determined by factors such as the size of the farm, the type of waste generated, and the methods used for waste treatment or disposal. For example, CAFOs typically require permits that Artikel specific waste management practices, including manure storage, land application, and monitoring requirements. Small farms might not require permits for composting or manure spreading, but they still need to adhere to local regulations.

- Permit Application Process: Obtaining a permit typically involves submitting an application to the relevant regulatory agency. The application must include detailed information about the farm’s operations, the types and quantities of waste generated, and the proposed waste management practices. This may also include a detailed site map, waste management plans, and environmental impact assessments. The permitting agency reviews the application and may conduct inspections to ensure compliance with regulations.

- Permit Conditions and Monitoring: Permits often come with specific conditions that farms must meet, such as limits on waste application rates, requirements for regular monitoring of soil and water quality, and provisions for record-keeping and reporting. Failure to comply with these conditions can result in penalties. For example, a farm with a permit for land application of manure might be required to monitor the nitrogen and phosphorus levels in the soil and submit regular reports to the permitting agency.

Penalties for Non-Compliance with Waste Management Regulations

Non-compliance with waste management regulations can result in significant penalties, ranging from fines to legal action. These penalties are designed to deter environmental damage and ensure that farms operate responsibly.

- Types of Penalties: Penalties for non-compliance can include financial fines, which can vary depending on the severity and frequency of the violation. Other penalties include warnings, corrective action orders, and suspension or revocation of permits. In severe cases, non-compliance can lead to criminal charges.

- Examples of Violations and Penalties: Examples of violations that can lead to penalties include improper manure storage leading to water contamination, illegal disposal of hazardous waste, exceeding permitted application rates for fertilizers, and failure to maintain required records. For instance, a farm that discharges untreated wastewater into a stream could face substantial fines and be required to remediate the environmental damage.

- Impact of Non-Compliance: Non-compliance not only results in financial and legal consequences but also can damage a farm’s reputation and erode public trust. It can also lead to environmental damage, such as water and soil contamination, which can harm ecosystems and human health. Moreover, non-compliance can affect the farm’s eligibility for government programs or subsidies.

Comparison of Waste Management Regulations Across Different Farming Operations

Waste management regulations vary significantly depending on the type of farming operation, reflecting the diverse nature of agricultural practices and the potential environmental impacts associated with each.

- Livestock Operations: Livestock operations, particularly CAFOs, face stringent regulations due to the large quantities of manure they generate. Regulations often focus on manure storage, land application, and nutrient management planning. For example, dairy farms are subject to specific regulations regarding manure storage capacity, runoff control, and the development of comprehensive nutrient management plans.

- Crop Production: Crop production operations are regulated primarily in terms of fertilizer and pesticide use, irrigation practices, and erosion control. Regulations may limit the application of fertilizers to prevent runoff into waterways or require the implementation of best management practices to reduce soil erosion.

- Specialty Farms: Specialty farms, such as fruit and vegetable farms, often have specific regulations related to food safety and water quality. Regulations may address the handling of produce, the use of irrigation water, and the disposal of crop residues. For example, farms that grow produce for human consumption may be required to adhere to the Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) standards, which include regulations for water quality testing and waste management practices.

Waste Reduction Strategies

Implementing effective waste reduction strategies is crucial for sustainable farm management. Minimizing waste not only benefits the environment but also enhances operational efficiency and can lead to significant cost savings. This section Artikels various approaches to reduce waste generation at the source, optimize resource utilization, and promote a circular economy within the farm ecosystem.

Minimizing Waste Generation at the Source

Preventative measures are the cornerstone of effective waste management. Focusing on reducing waste before it is even created is the most environmentally and economically sound approach. This involves a proactive strategy of planning, design, and implementation.

- Efficient Planning and Design: Careful planning of farm operations can significantly reduce waste. For example, consider the layout of fields to minimize travel distances for machinery, thereby reducing fuel consumption and emissions. Designing buildings with durability and adaptability in mind can extend their lifespan and reduce the need for frequent replacements.

- Optimizing Input Purchases: Buying only the necessary quantities of seeds, fertilizers, and other inputs prevents waste from expired products or improper storage. Bulk buying can be economical but requires careful consideration of storage capacity and potential for spoilage.

- Implementing Integrated Pest Management (IPM): IPM is a comprehensive approach that uses a combination of pest control methods, including biological control, cultural practices, and targeted pesticide applications. This reduces the reliance on broad-spectrum pesticides, minimizing chemical waste and its impact on the environment.

- Employee Training and Education: Training farm staff on proper handling, storage, and disposal of materials is essential. Educated employees are more likely to follow best practices, leading to fewer spills, leaks, and other incidents that generate waste.

- Regular Equipment Maintenance: Maintaining farm equipment in good working order prevents breakdowns and leaks of oil, fuel, and other fluids, which can contaminate soil and water. Regular maintenance also improves fuel efficiency, reducing emissions.

Optimizing Feed Management to Reduce Manure Production

Feed management plays a vital role in controlling the quantity and composition of manure. By optimizing feed rations and delivery methods, farmers can reduce the amount of undigested feed that ends up in manure, leading to a reduction in overall waste.

- Balancing Feed Rations: Providing animals with a balanced diet that meets their specific nutritional needs is critical. Overfeeding protein, for example, can result in excess nitrogen in manure, leading to environmental concerns. Using feed analysis to tailor rations to animal requirements helps minimize waste.

- Improving Feed Digestibility: Processing feed to improve digestibility can increase nutrient absorption, reducing the amount of undigested feed in manure. Techniques include grinding grains, pelleting feed, and using feed additives.

- Feeding Management Practices: Careful feeding practices, such as providing feed in multiple small meals, can improve feed efficiency. Preventing feed spoilage and spillage also reduces waste.

- Water Management: Providing clean, fresh water is crucial for animal health and feed utilization. Water restrictions or poor water quality can reduce feed intake and increase waste production.

- Use of Feed Additives: Certain feed additives, such as enzymes, can improve nutrient digestion and absorption. This leads to less undigested feed in manure.

Reducing Pesticide and Herbicide Usage

Minimizing the use of pesticides and herbicides is essential for protecting human health, wildlife, and the environment. Several strategies can be implemented to reduce reliance on these chemicals while maintaining crop yields.

- Crop Rotation: Rotating crops can disrupt pest and weed cycles, reducing the need for chemical control. Different crops have different vulnerabilities, and rotating them can help prevent the build-up of specific pests and weeds.

- Cover Cropping: Planting cover crops during fallow periods can suppress weeds, improve soil health, and reduce erosion. This reduces the need for herbicides.

- Biological Control: Introducing beneficial insects, such as ladybugs, to control pests is a natural and effective alternative to chemical pesticides.

- Scouting and Monitoring: Regularly monitoring fields for pests and weeds allows farmers to apply pesticides and herbicides only when and where they are needed. This targeted approach reduces overall chemical usage.

- Precision Application Technologies: Utilizing precision application technologies, such as GPS-guided sprayers, can ensure that chemicals are applied only to the targeted areas, minimizing waste and environmental impact.

Minimizing Packaging Waste

Packaging waste contributes significantly to the overall waste stream on farms. Implementing strategies to reduce and manage packaging waste can lead to significant environmental and economic benefits.

- Bulk Purchasing: Buying inputs in bulk, when feasible, reduces the amount of packaging waste generated. This is particularly effective for fertilizers, seeds, and animal feed.

- Reusable Packaging: Implementing systems for reusing packaging materials, such as totes or containers, can significantly reduce waste.

- Choosing Sustainable Packaging: When new packaging is required, selecting materials that are biodegradable, compostable, or made from recycled content is essential.

- Optimizing Packaging Design: Packaging design should be optimized to minimize material usage. Reducing the size and weight of packaging can decrease waste.

- Recycling Programs: Establishing on-farm recycling programs for paper, plastic, and other recyclable materials is crucial. This helps divert waste from landfills and conserves resources.

Manure Management Techniques

Effective manure management is crucial for sustainable farming practices, impacting both environmental protection and farm profitability. Proper techniques minimize pollution, conserve resources, and potentially generate valuable byproducts. This section will delve into various methods for managing manure, outlining their practical applications and benefits.

Manure Storage Methods

The selection of a manure storage method depends on factors like farm size, climate, available land, and regulatory requirements. Several common methods are employed, each with its own advantages and disadvantages.

Open Lagoons

Open lagoons are large, earthen basins designed to store liquid manure. These lagoons rely on anaerobic decomposition, a process where microorganisms break down organic matter in the absence of oxygen.

- Advantages: Open lagoons offer significant storage capacity, accommodating large volumes of manure. They can be relatively inexpensive to construct initially, particularly in areas with suitable soil conditions. They also reduce the need for frequent manure handling.

- Disadvantages: Open lagoons can emit significant greenhouse gases, including methane and nitrous oxide. They also release odors, which can be a nuisance to neighboring communities. Potential for groundwater contamination exists if the lagoon liner fails. Nutrient runoff from the lagoon, especially nitrogen and phosphorus, can pollute surface water.

Covered Lagoons

Covered lagoons are similar to open lagoons but incorporate a cover, typically made of synthetic materials. This cover traps gases, including methane, which can then be collected and used as a renewable energy source.

- Advantages: Covered lagoons significantly reduce odor emissions and greenhouse gas emissions compared to open lagoons. They provide an opportunity to capture biogas, a valuable renewable energy source. They also minimize rainfall infiltration and prevent the escape of nutrients, thereby reducing the risk of water pollution.

- Disadvantages: Covered lagoons have higher construction costs than open lagoons. The cover requires regular maintenance and can be susceptible to damage. Biogas collection systems require specialized equipment and expertise. The management of the biogas produced must be carefully considered.

Solid Manure Storage

Solid manure storage involves piling or stacking manure in a designated area. This method is suitable for manure with a higher solid content, such as that produced by beef cattle or horses.

- Advantages: Solid manure storage is generally less expensive to construct than lagoons. It can be a simple and effective way to manage manure on smaller farms. It also allows for the natural composting of the manure, enhancing its value as a soil amendment.

- Disadvantages: Solid manure storage can generate odors, especially during warm weather. Runoff from manure piles can pollute surface and groundwater. The handling and spreading of solid manure can be labor-intensive. The potential for pest problems, such as flies, exists.

Procedure for Composting Manure

Composting is a controlled biological process that transforms organic waste, including manure, into a stable, humus-like substance called compost. Compost is a valuable soil amendment that improves soil structure, water retention, and nutrient availability.

The composting process involves several key steps:

- Feedstock Preparation: Combine manure with a carbon-rich bulking agent, such as wood chips, straw, or shredded paper. This provides the necessary carbon-to-nitrogen ratio for effective composting and improves aeration. The ideal carbon-to-nitrogen ratio is typically between 25:1 and 30:1.

- Pile Construction: Construct the compost pile in a well-drained area. The pile should be large enough to retain heat but not so large that it becomes anaerobic. A typical pile size is 4-8 feet high, 10-15 feet wide, and as long as needed.

- Aeration: Provide adequate aeration to the compost pile. This can be achieved by turning the pile regularly (e.g., weekly) or by using forced aeration systems. Aeration is essential for the aerobic decomposition process.

- Moisture Management: Maintain optimal moisture levels in the compost pile, typically between 50% and 60%. The moisture content can be checked by squeezing a handful of compost; it should feel like a wrung-out sponge.

- Temperature Monitoring: Monitor the temperature of the compost pile regularly. The temperature should rise to 130-160°F (54-71°C) to kill pathogens and weed seeds.

- Curing: After the active composting phase, allow the compost to cure for several weeks or months. During curing, the compost stabilizes and further breaks down.

- Application: Apply the finished compost to fields as a soil amendment.

Considerations for Composting:

- Manure Type: Different types of manure have varying nutrient contents and require different bulking agents.

- Climate: Temperature and rainfall can affect the composting process.

- Odor Control: Proper aeration and moisture management can minimize odor emissions.

- Regulations: Composting operations may be subject to local or state regulations.

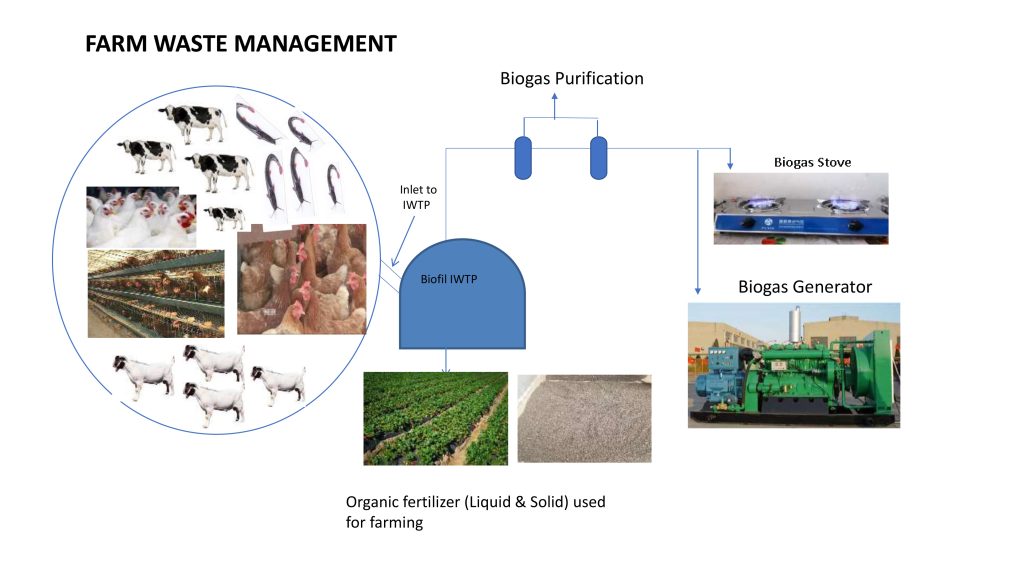

Anaerobic Digestion of Manure

Anaerobic digestion (AD) is a biological process where microorganisms break down organic matter in the absence of oxygen, producing biogas (primarily methane and carbon dioxide) and digestate. Biogas can be used as a renewable energy source, and digestate can be used as a fertilizer.

The anaerobic digestion process includes these stages:

- Pretreatment: Manure may be pretreated to remove large solids or to adjust its consistency.

- Digestion: Manure is fed into an airtight digester, where anaerobic microorganisms break down the organic matter.

- Biogas Production: Biogas, a mixture of methane and carbon dioxide, is produced during the digestion process.

- Digestate Separation: The remaining solid and liquid fractions of the digestate can be separated.

- Biogas Utilization: Biogas can be used to generate electricity, heat, or combined heat and power (CHP).

- Digestate Utilization: The digestate can be used as a fertilizer or further processed.

Benefits of Anaerobic Digestion:

- Renewable Energy Production: AD generates biogas, a renewable energy source that can replace fossil fuels.

- Odor Reduction: AD significantly reduces odor emissions from manure.

- Pathogen Reduction: AD reduces pathogens in manure, improving its safety for use as a fertilizer.

- Nutrient Recovery: AD concentrates nutrients in the digestate, making it a more effective fertilizer.

- Waste Reduction: AD reduces the volume of manure that needs to be managed.

- Environmental Benefits: AD reduces greenhouse gas emissions and can contribute to climate change mitigation.

Example: In the United States, a 2019 study by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) indicated that anaerobic digestion systems on farms can reduce greenhouse gas emissions by up to 90% compared to traditional manure management practices. These systems also provide economic benefits by generating renewable energy and reducing the need for synthetic fertilizers. Real-world examples include large dairy farms in California and Wisconsin that utilize anaerobic digesters to generate electricity and sell it back to the grid, demonstrating the economic viability and environmental benefits of this technology.

Composting and Vermicomposting

Composting and vermicomposting offer sustainable methods for managing farm waste, transforming organic materials into valuable soil amendments. These processes not only reduce waste volume but also create nutrient-rich products that can improve soil health and reduce the need for synthetic fertilizers. They are environmentally friendly alternatives that contribute to a circular economy on the farm.

Principles of Composting

Composting is a natural process where microorganisms, including bacteria and fungi, break down organic matter in the presence of oxygen. This biological decomposition converts waste into a stable, humus-rich substance called compost. The process relies on the activity of various microorganisms that thrive under specific conditions.The key components of composting include:

- Carbon-rich materials (browns): These provide energy for the microorganisms. Examples include dry leaves, straw, wood chips, and shredded paper.

- Nitrogen-rich materials (greens): These provide the building blocks for microbial growth. Examples include food scraps, grass clippings, and manure.

- Moisture: Water is essential for microbial activity.

- Oxygen: Aeration is necessary for aerobic decomposition, preventing the production of foul odors.

- Microorganisms: These are the decomposers, breaking down organic matter.

The composting process can be summarized by the following equation:

Organic Matter + Oxygen + Water + Microorganisms → Compost + Carbon Dioxide + Heat

The heat generated during composting is a byproduct of microbial activity, and it plays a crucial role in breaking down pathogens and weed seeds. The final product, compost, is a dark, crumbly material that improves soil structure, water retention, and nutrient availability.

Setting Up a Compost Pile

Setting up a compost pile involves careful planning and execution to ensure efficient decomposition. The following steps provide a guide for creating a successful compost system:

- Choose a Location: Select a well-drained area, preferably in a shady location, to prevent the compost from drying out. Consider the accessibility for adding materials and turning the pile.

- Gather Materials: Collect a mix of carbon-rich (brown) and nitrogen-rich (green) materials. Aim for a carbon-to-nitrogen ratio of approximately 25:1 to 30:1.

- Build the Pile: Start with a base layer of coarse, carbon-rich materials to improve aeration. Alternate layers of browns and greens, moistening each layer as you build.

- Maintain Moisture: The compost pile should be as moist as a wrung-out sponge. Water the pile regularly, especially during dry periods.

- Aerate the Pile: Turn the pile regularly (every one to two weeks) to provide oxygen and prevent anaerobic conditions. You can use a pitchfork or a compost turner.

- Monitor the Temperature: The temperature inside the pile should rise to between 130°F and 160°F (54°C and 71°C) to kill pathogens and weed seeds. Use a compost thermometer to monitor the temperature.

- Wait for the Compost to Mature: The composting process can take anywhere from a few months to a year, depending on the size of the pile, the materials used, and the maintenance practices. The compost is ready when it is dark, crumbly, and has an earthy smell.

Maintaining Optimal Composting Conditions

Maintaining optimal conditions is essential for efficient composting. Several factors influence the success of the process.

- Moisture Content: Maintaining the correct moisture level is crucial. The pile should be moist but not soggy. Check the moisture level by squeezing a handful of compost; it should feel like a damp sponge.

- Aeration: Regular turning provides oxygen to the microorganisms. Insufficient oxygen can lead to anaerobic conditions, producing foul odors and slowing down the decomposition process.

- Carbon-to-Nitrogen Ratio: A balanced ratio of carbon-rich and nitrogen-rich materials is essential for microbial activity. A ratio that is too high in carbon can slow down the process, while a ratio that is too high in nitrogen can cause unpleasant odors.

- Temperature: The ideal temperature range for composting is between 130°F and 160°F (54°C and 71°C). Monitor the temperature using a compost thermometer and adjust the pile management practices accordingly.

- Particle Size: Smaller particle sizes decompose faster than larger ones. Chop or shred materials to increase the surface area available for microbial action.

Vermicomposting Guide for Farm Waste

Vermicomposting, or worm composting, is a method of composting that uses worms, typically red wigglers ( Eisenia fetida), to break down organic waste. This process produces nutrient-rich compost and a liquid fertilizer called “worm tea.” It’s an efficient and effective method for processing organic farm waste.The following is a step-by-step guide for setting up and maintaining a vermicomposting system:

- Choose a Worm Bin: You can use a variety of containers, such as plastic bins, wooden boxes, or commercially available worm composting systems. Ensure the bin has drainage holes and a lid to retain moisture and prevent pests.

- Prepare the Bedding: The bedding provides a comfortable habitat for the worms and absorbs excess moisture. Use a mixture of shredded paper, cardboard, coconut coir, or peat moss. Moisten the bedding before adding the worms.

- Introduce the Worms: Red wigglers are the best choice for vermicomposting. Start with about 1,000 worms per pound of waste added per week.

- Add Food Waste: Bury food waste, such as fruit and vegetable scraps, coffee grounds, and tea bags, under the bedding. Avoid adding meat, dairy products, oily foods, and citrus fruits in large quantities.

- Maintain Moisture: Keep the bedding moist but not soggy. The worms need moisture to survive and thrive.

- Aerate the Bin: Worms need oxygen. Ensure proper aeration by occasionally fluffing the bedding and food waste.

- Harvest the Compost: Once the bedding and food waste have been converted into compost, typically after several months, harvest the compost. There are several methods, including moving the worms to one side of the bin and harvesting the compost from the other side.

- Collect Worm Tea: Worm tea is a liquid fertilizer produced by the vermicomposting process. Collect the leachate from the drainage holes and dilute it with water before using it to fertilize plants.

Vermicomposting can be used to manage various types of farm waste, including food scraps, manure, and crop residues. For example, a study by the University of California, Davis, found that vermicomposting effectively reduced the volume of food waste from dining halls, while producing high-quality compost for landscaping.

Liquid Waste Management

Effective liquid waste management is crucial for maintaining a sustainable farm operation. Liquid waste, often overlooked, can pose significant environmental risks if not handled properly. This section details various methods for managing liquid waste, including wastewater from washing and processing, offering practical solutions for treatment and responsible disposal.

Methods for Managing Liquid Waste

Several methods are employed to manage liquid waste on farms, each with its advantages and disadvantages. The choice of method depends on factors such as the volume of waste, the type of contaminants, and available resources.

- Wastewater Treatment Ponds: These are large, shallow ponds designed to treat wastewater through natural processes. They rely on sedimentation, biological activity, and sunlight to reduce pollutants. These are particularly suitable for treating wastewater from livestock operations.

- Constructed Wetlands: Constructed wetlands are engineered systems that mimic natural wetlands to treat wastewater. They utilize plants, soil, and microorganisms to filter and break down pollutants. These are versatile and can be designed to treat a variety of wastewater types.

- Filtration Systems: Filtration systems use physical barriers to remove solid particles and other contaminants from wastewater. These can range from simple sand filters to more advanced membrane filtration systems. They are often used as a pre-treatment step before other treatment methods.

- Anaerobic Digestion: This process involves breaking down organic matter in the absence of oxygen, producing biogas (primarily methane) and a digestate. The biogas can be used for energy, while the digestate can be used as fertilizer. This method is effective for treating wastewater with high organic loads.

- Aerobic Treatment Systems: These systems use oxygen to break down organic matter in wastewater. This can involve activated sludge systems, trickling filters, or aerated lagoons. Aerobic systems are generally more effective at removing pollutants than anaerobic systems, but they require more energy.

Constructing a Constructed Wetland for Wastewater Treatment

Constructed wetlands provide an effective and environmentally friendly method for treating wastewater. Building one requires careful planning and execution.

- Site Selection: Choose a site with suitable soil permeability (low permeability is preferable to prevent water from seeping into the ground) and sufficient sunlight. Consider the proximity to the wastewater source and the final discharge location.

- Design and Layout: Design the wetland based on the volume and characteristics of the wastewater. Determine the size, shape, and depth of the wetland cells. A typical design involves multiple cells, each with a different function (e.g., settling, filtration, polishing). Consider the use of different plant species for optimal treatment.

- Excavation and Liner Installation: Excavate the wetland cells to the designed depth. Install a liner (e.g., clay, synthetic membrane) to prevent water from leaching into the soil.

- Media and Planting: Fill the cells with a suitable media, such as gravel, sand, and soil. Plant wetland plants that are effective at removing pollutants. Common choices include cattails, reeds, and bulrushes.

- Plumbing and Control Structures: Install pipes and control structures to direct wastewater into the wetland and allow for outflow. Consider the use of a distribution system to evenly distribute the wastewater across the wetland.

- Operation and Maintenance: Regularly monitor the water quality and plant health. Remove accumulated solids and debris as needed. Harvest plants when appropriate.

Guidelines for the Safe Application of Treated Wastewater to Land

The safe application of treated wastewater to land is essential to prevent environmental contamination and protect human health. Adhering to specific guidelines is critical.

- Water Quality Standards: Ensure the treated wastewater meets all relevant water quality standards before application. These standards vary depending on the intended use of the water and local regulations.

- Soil Testing: Conduct soil testing to determine the soil’s ability to accept the wastewater and to assess the nutrient levels. Avoid over-application, which can lead to soil saturation and nutrient runoff.

- Application Rates: Determine appropriate application rates based on the wastewater’s nutrient content, the soil type, and the crop’s nutrient requirements. Over-application can lead to groundwater contamination and soil salinization.

- Crop Selection: Choose crops that are suitable for irrigation with treated wastewater. Consider the crop’s tolerance to specific contaminants and the potential for bioaccumulation.

- Buffer Zones: Maintain appropriate buffer zones between the application area and sensitive areas, such as water bodies, wells, and residential areas. These buffer zones help to prevent runoff and protect water quality.

- Monitoring and Record Keeping: Regularly monitor the water quality, soil conditions, and crop health. Maintain detailed records of wastewater application rates, dates, and locations.

The Role of Filtration and Sedimentation in Liquid Waste Treatment

Filtration and sedimentation are fundamental processes in liquid waste treatment, acting as initial steps to remove solid particles and reduce the overall pollutant load.

- Sedimentation: This process involves allowing solid particles to settle out of the wastewater by gravity. Sedimentation tanks are designed to provide sufficient detention time for the particles to settle. The settled solids, known as sludge, are then removed and treated separately.

- Filtration: Filtration removes suspended solids and other particles that did not settle during sedimentation. Common filtration methods include:

- Sand Filters: These filters use layers of sand to trap particles.

- Gravel Filters: Gravel filters use layers of gravel to remove larger particles.

- Membrane Filters: These filters use membranes with very small pores to remove even the smallest particles and dissolved substances.

- Benefits: Filtration and sedimentation are essential for:

- Reducing the amount of solid waste that needs further treatment.

- Protecting downstream treatment processes from clogging or damage.

- Improving the overall efficiency of the treatment system.

- Reducing the levels of pollutants in the treated water.

Recycling and Reuse of Farm Waste

Farm waste, when managed strategically, transcends its classification as a disposal problem and transforms into a valuable resource. Recycling and reuse practices are fundamental to sustainable agriculture, minimizing environmental impact and enhancing farm profitability. This section explores the various methods and opportunities available for repurposing farm waste materials, promoting a circular economy on the farm.

Identifying Opportunities for Recycling Farm Waste Materials

Recycling on the farm extends beyond conventional practices, encompassing the repurposing of diverse materials generated through agricultural operations. This involves identifying and segregating waste streams to facilitate efficient processing and reuse.

- Plastics: Agricultural plastics, such as silage wrap, irrigation pipes, and seedling trays, represent a significant waste stream. Recycling options include collection programs offered by municipalities or private companies specializing in agricultural plastic recycling. The collected plastics are often cleaned, processed, and transformed into new products like plastic lumber, drainage pipes, or even new agricultural films.

- Metals: Scrap metal from equipment repair, discarded machinery, and metal packaging can be valuable for recycling. Ferrous metals (steel, iron) and non-ferrous metals (aluminum, copper) are commonly recycled. Recycling facilities process these metals, melting them down to create new metal products, reducing the need for virgin materials and conserving energy.

- Glass: While less common, glass containers used for agrochemicals or other farm supplies can be recycled in some regions. Glass recycling reduces landfill waste and the need for new glass production.

- Paper and Cardboard: Cardboard boxes used for packaging and paper products can be recycled through local recycling programs. Recycled paper can be used for animal bedding, compost amendments, or for producing new paper products.

Reusing Crop Residues

Crop residues, the non-harvested portions of crops, represent a significant source of organic matter that can be repurposed on the farm. Proper management of these residues is essential for soil health and resource efficiency.

- Animal Bedding: Straw, hay, and corn stalks are commonly used as bedding for livestock. This provides a comfortable environment for animals and, after use, the manure-laden bedding can be composted or applied to fields as a soil amendment, improving soil fertility and structure.

- Soil Amendments: Crop residues can be incorporated directly into the soil or composted to improve soil organic matter content, water retention, and nutrient availability. This reduces the need for synthetic fertilizers and enhances soil health.

- Mulch: Crop residues, such as straw and shredded stalks, can be used as mulch around crops to suppress weeds, conserve moisture, and regulate soil temperature. This reduces the need for herbicides and irrigation.

- Erosion Control: Crop residues left on the soil surface can help to protect the soil from erosion, particularly on sloped land. This is especially important during periods of heavy rainfall or strong winds.

Turning Waste into Useful Products

Converting farm waste into valuable products is a key aspect of a circular economy approach. This involves various processes that transform waste materials into resources that can be used on the farm or sold for profit.

- Composting: Organic waste, including crop residues, animal manure, and food scraps, can be composted to produce a nutrient-rich soil amendment. Composting reduces the volume of waste, eliminates pathogens, and creates a valuable product for improving soil health.

- Vermicomposting: Earthworms are used to decompose organic waste, producing a nutrient-rich fertilizer called vermicast or worm castings. Vermicomposting is particularly effective for processing food waste and manure, creating a valuable soil amendment and liquid fertilizer.

- Anaerobic Digestion: Anaerobic digestion breaks down organic matter in the absence of oxygen, producing biogas (primarily methane) and digestate. Biogas can be used as a renewable energy source for heating, electricity generation, or vehicle fuel. Digestate is a nutrient-rich fertilizer.

- Biochar Production: Biochar is a charcoal-like substance produced by heating biomass in the absence of oxygen (pyrolysis). Biochar can be used as a soil amendment to improve soil fertility, water retention, and carbon sequestration.

Creating a Closed-Loop System on a Farm

A closed-loop system on a farm aims to minimize waste and maximize resource utilization by integrating various practices that transform waste into valuable resources. This promotes sustainability, reduces environmental impact, and enhances farm efficiency.

- Integrating Livestock and Crop Production: Livestock manure can be used as fertilizer for crops, and crop residues can be used as animal feed or bedding, creating a cyclical flow of nutrients and resources.

- Composting and Vermicomposting: These processes convert organic waste into valuable soil amendments, reducing the need for synthetic fertilizers and improving soil health.

- Anaerobic Digestion: This process can be integrated to generate renewable energy from manure and organic waste, reducing reliance on fossil fuels and producing a nutrient-rich digestate for fertilizer.

- Water Harvesting and Reuse: Implementing systems to collect and reuse rainwater or greywater for irrigation or other farm operations can conserve water resources and reduce reliance on external water sources.

- Cover Cropping: Planting cover crops can help to improve soil health, reduce erosion, suppress weeds, and provide biomass for composting or animal feed, further enhancing the closed-loop system.

On-Farm Waste Treatment Technologies

Implementing effective on-farm waste treatment technologies is crucial for minimizing environmental impact, complying with regulations, and potentially recovering valuable resources. These technologies transform waste materials, reducing pollution and often generating usable byproducts like energy or fertilizer. This section explores various on-farm waste treatment options, providing details on their operation, applications, benefits, and limitations.

Biogas Digesters

Biogas digesters are closed systems that anaerobically digest organic waste, such as animal manure and crop residues, to produce biogas (primarily methane and carbon dioxide) and digestate (a nutrient-rich byproduct).The process involves several stages:

- Pre-treatment: Waste is often pre-treated by grinding or mixing to enhance digestion.

- Anaerobic Digestion: Microorganisms break down the organic matter in the absence of oxygen. This process converts complex organic molecules into simpler ones, ultimately producing biogas.

- Biogas Collection: The biogas produced is collected and stored.

- Digestate Management: The remaining digestate is a nutrient-rich liquid or solid that can be used as fertilizer.

Biogas digesters offer several applications:

- Energy Production: Biogas can be used for heating, cooking, and electricity generation. The biogas can fuel a combined heat and power (CHP) system, providing both electricity and heat.

- Fertilizer Production: The digestate is a valuable fertilizer, reducing the need for synthetic fertilizers.

- Waste Reduction: Reduces the volume and odor of manure and other organic wastes.

- Reduced Greenhouse Gas Emissions: Capturing and utilizing methane, a potent greenhouse gas, reduces its release into the atmosphere.

The benefits of biogas digesters include:

- Renewable Energy Source: Provides a sustainable source of energy.

- Reduced Environmental Impact: Minimizes pollution from waste disposal.

- Improved Nutrient Management: Converts waste into valuable fertilizer.

- Potential for Economic Benefits: Reduces energy costs and generates revenue from biogas sales.

The limitations of biogas digesters include:

- High Initial Investment: Can be expensive to install.

- Operational Complexity: Requires careful management and maintenance.

- Temperature Sensitivity: Digestion efficiency is affected by temperature fluctuations.

- Feedstock Requirements: Requires consistent and suitable organic waste inputs.

A study by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) demonstrated that a typical anaerobic digester on a dairy farm with 1,000 cows could generate enough electricity to power approximately 250 homes annually, while also reducing greenhouse gas emissions equivalent to removing 1,000 cars from the road. This example underscores the potential of biogas digesters to transform agricultural waste into a valuable resource while mitigating environmental impact.

Filtration Systems for Water Treatment

Filtration systems are essential for treating water contaminated by farm activities, such as runoff from animal housing or irrigation return flows. These systems remove pollutants, protecting water quality and enabling reuse of water resources.Various filtration technologies are used:

- Sedimentation: This is the simplest form of filtration. It involves allowing water to sit in a tank, allowing heavier particles to settle at the bottom.

- Sand Filters: These filters use layers of sand to remove suspended solids. Water is passed through the sand, trapping particles.

- Activated Carbon Filters: These filters use activated carbon to remove organic contaminants, pesticides, and odors. The activated carbon adsorbs these pollutants.

- Membrane Filtration: This includes microfiltration, ultrafiltration, nanofiltration, and reverse osmosis. These systems use membranes with increasingly small pore sizes to remove a wide range of contaminants, including dissolved solids and bacteria. Reverse osmosis is particularly effective at removing salts and other dissolved minerals.

The benefits of filtration systems include:

- Improved Water Quality: Removes pollutants and contaminants.

- Water Reuse: Allows for the reuse of water for irrigation, livestock watering, and other purposes.

- Environmental Protection: Reduces the discharge of pollutants into water bodies.

- Compliance with Regulations: Helps farms meet water quality standards.

The limitations of filtration systems include:

- Cost: Can be expensive to install and maintain, particularly for advanced filtration systems.

- Maintenance Requirements: Requires regular cleaning, backwashing, and replacement of filter media.

- Energy Consumption: Some filtration systems, such as reverse osmosis, consume significant energy.

- Waste Generation: Filtration processes can generate waste, such as sludge or concentrated brine, that requires proper disposal.

For example, a farm using a sand filtration system to treat irrigation runoff can reduce sediment levels by up to 90%, improving water quality and reducing the risk of soil erosion. This illustrates the practical impact of filtration systems in agricultural settings. Furthermore, a reverse osmosis system might be used in regions with high salinity to desalinate water for livestock and irrigation, ensuring water suitable for agricultural purposes.

The Economics of Farm Waste Management

Managing farm waste effectively isn’t just about environmental responsibility; it’s also a crucial aspect of financial sustainability. Understanding the economic implications of different waste management practices is essential for making informed decisions that can reduce costs, generate revenue, and improve overall farm profitability. This section delves into the financial aspects of farm waste management, providing practical insights and strategies for optimizing your farm’s economic performance.

Costs Associated with Different Waste Management Practices

The costs associated with farm waste management vary significantly depending on the chosen methods, farm size, and local regulations. It’s crucial to conduct a thorough cost analysis to determine the most economically viable options for your specific operation.

- Collection and Storage: Initial investments include the purchase or construction of storage facilities like manure sheds, lagoons, or composting bins. Ongoing costs encompass labor, equipment maintenance, and the cost of electricity for aeration systems or pumping.

- Transportation: Hauling waste off-site for disposal or processing incurs expenses related to fuel, vehicle maintenance, and labor. Distances to processing facilities or landfills significantly impact transportation costs.

- Treatment: Technologies like anaerobic digestion or wastewater treatment plants involve substantial upfront investments in equipment and infrastructure. Recurring costs include energy consumption, chemical usage, and specialized labor for operation and maintenance.

- Disposal: Landfilling is often the least expensive option initially but carries long-term costs, including tipping fees and potential environmental remediation expenses if leachate contaminates the soil or groundwater.

- Permitting and Compliance: Meeting regulatory requirements often necessitates fees for permits, environmental impact assessments, and regular monitoring. Non-compliance can result in substantial fines and legal expenses.

Strategies for Reducing Waste Management Expenses

Implementing effective strategies can significantly lower waste management costs, enhancing the farm’s bottom line.

- Waste Reduction at the Source: Implementing best practices for animal feeding, optimizing feed conversion rates, and preventing feed wastage can drastically reduce the volume of waste generated. This minimizes the need for expensive treatment or disposal methods.

- Efficient Storage and Handling: Proper storage design and efficient handling practices can reduce labor costs, minimize spills, and prevent the loss of valuable nutrients. Investing in efficient equipment, such as manure spreaders, can also improve operational efficiency.

- Composting and Vermicomposting: These methods transform waste into valuable soil amendments, reducing disposal costs and potentially generating revenue through the sale of compost or vermicompost.

- Anaerobic Digestion: While requiring a significant initial investment, anaerobic digestion can convert waste into biogas, which can be used for electricity generation or heating, offsetting energy costs. The digestate produced can also be used as a fertilizer, reducing the need for purchased fertilizers.

- Negotiating with Service Providers: Exploring options for bulk discounts, negotiating favorable terms with waste haulers or processors, and comparing quotes from multiple service providers can lead to cost savings.

Economic Benefits of Waste Reduction and Reuse

Focusing on waste reduction and reuse can unlock significant economic benefits, transforming waste from a liability into a resource.

- Reduced Disposal Costs: Minimizing waste generation directly translates to lower disposal fees, whether through landfilling or off-site processing.

- Revenue Generation: Selling compost, vermicompost, or biogas can create new revenue streams for the farm.

- Reduced Fertilizer Costs: Utilizing manure and digestate as fertilizers reduces the need for purchasing expensive commercial fertilizers.

- Improved Soil Health: Applying compost and other organic amendments improves soil structure, water retention, and nutrient availability, leading to increased crop yields and reduced reliance on synthetic inputs.

- Enhanced Farm Image: Implementing sustainable waste management practices can improve the farm’s public image, attracting environmentally conscious consumers and potentially increasing product sales.

Demonstrating How to Calculate the Return on Investment for a Waste Management Project

Calculating the Return on Investment (ROI) is crucial for evaluating the financial viability of a waste management project. This involves comparing the initial investment costs with the anticipated benefits over the project’s lifespan.

The basic formula for ROI is:

ROI = ((Net Profit / Cost of Investment) – 100)

Where:

- Net Profit: Total revenue generated from the project minus all associated costs.

- Cost of Investment: The total initial investment, including equipment, installation, and permitting costs.

Example: A dairy farm invests $50,000 in a composting system. The annual benefits include a $5,000 reduction in fertilizer costs, $3,000 in reduced waste hauling fees, and $2,000 in revenue from compost sales. Annual operating costs for the compost system are $1,000.

Calculation:

- Net Profit = ($5,000 + $3,000 + $2,000)

-$1,000 = $9,000 - ROI = (($9,000 / $50,000)

– 100) = 18%

This indicates that the composting system generates a 18% return on the initial investment annually. A higher ROI suggests a more financially attractive project.

Implementing a Farm Waste Management Plan

Implementing a comprehensive farm waste management plan is crucial for environmental stewardship, regulatory compliance, and operational efficiency. A well-structured plan provides a roadmap for effectively managing waste, minimizing environmental impact, and potentially generating valuable resources. This section Artikels the key components, implementation steps, and evaluation strategies for developing and maintaining a successful farm waste management plan.

Template for a Comprehensive Farm Waste Management Plan

A template provides a standardized framework for organizing information and ensuring all essential aspects of waste management are addressed. This structured approach facilitates clear communication, consistent monitoring, and effective decision-making.The template should include the following sections:

- Farm Overview: This section should include a description of the farm, its size, location, type of operations (e.g., livestock, crops, mixed), and the number of animals or acreage. It also specifies the primary agricultural products produced.

- Waste Inventory: A detailed inventory of all waste streams generated on the farm, including manure, crop residues, dead animals, packaging materials, and any other waste products. This includes the estimated quantities and characteristics (e.g., composition, moisture content) of each waste stream. Consider seasonal variations in waste generation.

- Regulatory Requirements: A summary of all relevant local, state, and federal regulations pertaining to farm waste management. This includes permits, licenses, and any specific requirements for handling, storage, treatment, and disposal of different waste types.

- Waste Management Goals and Objectives: Clearly defined goals and objectives for waste management, such as reducing waste volume, minimizing environmental impact, improving resource utilization, and complying with regulations. These goals should be specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART).

- Waste Management Strategies: A detailed description of the strategies to be implemented for each waste stream. This should include information on waste reduction, reuse, recycling, treatment (e.g., composting, anaerobic digestion), and disposal methods.

- Infrastructure and Equipment: A list of all existing and planned infrastructure and equipment required for waste management, such as storage facilities, composting systems, treatment plants, and transportation vehicles. This includes specifications, capacity, and maintenance schedules.

- Operating Procedures: Detailed operating procedures for all waste management activities, including handling, storage, treatment, and disposal. These procedures should include safety protocols, best management practices, and emergency response plans.

- Monitoring and Record Keeping: A system for monitoring and recording key parameters, such as waste quantities, treatment efficiency, environmental impacts, and regulatory compliance. This includes a schedule for monitoring, the parameters to be monitored, and the methods for data collection and analysis.

- Training and Education: A plan for training farm personnel on waste management practices, safety procedures, and regulatory requirements. This includes the topics to be covered, the frequency of training, and the methods for evaluating training effectiveness.

- Budget and Financial Analysis: A budget for waste management activities, including capital costs, operating costs, and potential revenue streams (e.g., from the sale of compost or biogas). This section should also include a financial analysis to assess the economic viability of the plan.

- Contingency Planning: A contingency plan to address potential problems, such as equipment failures, natural disasters, and regulatory changes. This includes backup plans, alternative waste management methods, and emergency response procedures.

- Plan Review and Updates: A schedule for reviewing and updating the plan regularly, to ensure its effectiveness and relevance. This should include a process for incorporating new information, regulatory changes, and technological advancements.

Key Components of a Successful Plan

Several critical elements contribute to the effectiveness of a farm waste management plan. These components work together to ensure that waste is managed efficiently, sustainably, and in compliance with regulations.

- Commitment from Management and Staff: Successful implementation requires strong commitment from farm management and active participation from all staff members. Training, communication, and accountability are crucial for fostering a culture of environmental responsibility.

- Waste Minimization Strategies: Prioritizing waste reduction is essential. This involves implementing practices such as reducing feed waste, optimizing fertilizer use, and using durable packaging materials. Implementing source reduction can significantly decrease the volume of waste that needs to be managed.

- Appropriate Waste Handling and Storage: Proper handling and storage of waste are critical to prevent environmental contamination and protect human health. This includes using appropriate storage facilities (e.g., covered manure storage, composting bins), following safe handling procedures, and preventing spills and leaks.

- Treatment and Processing Options: Selecting appropriate treatment and processing methods is important, such as composting, anaerobic digestion, and other technologies. The choice of methods should be based on the type and quantity of waste, environmental regulations, and economic considerations.

- Regular Monitoring and Record Keeping: Consistent monitoring and detailed record-keeping are essential for evaluating the effectiveness of the plan, identifying areas for improvement, and demonstrating compliance with regulations. This includes tracking waste quantities, treatment performance, and environmental impacts.

- Flexibility and Adaptability: A successful plan should be flexible and adaptable to changing conditions, such as new regulations, technological advancements, and market opportunities. Regular review and updates are essential to ensure the plan remains effective over time.

- Community Engagement: Involving the local community can build trust and support for the farm’s waste management practices. This can include providing information about the plan, addressing concerns, and participating in community initiatives.

Timeline for Implementing a Waste Management Plan

A well-defined timeline is essential for guiding the implementation of a farm waste management plan. The timeline provides a structured approach, ensures that tasks are completed on schedule, and helps to monitor progress.A sample timeline might include the following phases:

- Phase 1: Planning and Assessment (1-3 months)

- Conduct a thorough farm assessment and waste inventory.

- Research and identify relevant regulations and best management practices.

- Develop waste management goals and objectives.

- Create the farm waste management plan template.

- Phase 2: Plan Development and Approval (2-4 months)

- Draft the comprehensive farm waste management plan.

- Seek input from farm staff, consultants, and regulatory agencies.

- Finalize the plan and obtain necessary approvals.

- Phase 3: Implementation and Training (3-6 months)

- Implement waste management practices, including new infrastructure and equipment.

- Train farm staff on waste management procedures and safety protocols.

- Establish monitoring and record-keeping systems.

- Phase 4: Monitoring, Evaluation, and Optimization (Ongoing)

- Regularly monitor waste quantities, treatment performance, and environmental impacts.

- Evaluate the effectiveness of the plan and identify areas for improvement.

- Make adjustments to the plan as needed, based on monitoring data and feedback.

- Conduct regular reviews and updates of the plan.

The timeline’s specific duration will vary depending on the farm’s size, complexity, and the scope of the waste management plan. Large-scale farms or those requiring significant infrastructure changes may need a longer implementation period.

Methods for Monitoring and Evaluating the Effectiveness of the Plan

Regular monitoring and evaluation are essential to ensure that the farm waste management plan is achieving its objectives and complying with regulations. These processes provide valuable data for identifying areas for improvement and making informed decisions.The following are some key methods for monitoring and evaluating plan effectiveness:

- Waste Quantity and Composition Analysis: Regularly measure and record the quantities of each waste stream generated on the farm. Analyze the composition of the waste (e.g., nutrient content, moisture content) to assess its characteristics and potential for reuse or treatment. This data helps to identify trends, track progress towards waste reduction goals, and optimize treatment processes.

- Treatment Performance Monitoring: Monitor the performance of waste treatment systems, such as composting piles or anaerobic digesters. Measure key parameters, such as temperature, pH, and nutrient levels, to ensure that the systems are operating efficiently and effectively. This includes the quality of the final product (e.g., compost) and its suitability for use.

- Environmental Monitoring: Monitor environmental parameters to assess the impact of waste management practices. This can include monitoring water quality (e.g., testing for nutrient runoff), air quality (e.g., measuring ammonia emissions), and soil quality (e.g., assessing nutrient levels and soil health). Environmental monitoring data helps to identify potential problems and ensure compliance with environmental regulations.

- Regulatory Compliance Audits: Conduct regular audits to ensure compliance with all relevant regulations. This includes reviewing permits, licenses, and operating procedures. Maintain detailed records of all waste management activities to demonstrate compliance.

- Financial Analysis: Regularly review the budget and financial performance of the waste management plan. Track costs, revenue streams, and the return on investment (ROI) of waste management practices. This helps to assess the economic viability of the plan and identify opportunities for cost savings or revenue generation.

- Staff Feedback and Training Evaluation: Obtain feedback from farm staff on the effectiveness of waste management practices and training programs. Conduct regular training sessions to ensure that staff members are up-to-date on best practices and safety procedures. Evaluate the effectiveness of training programs to identify areas for improvement.

- External Audits and Reviews: Consider conducting periodic audits or reviews by external experts or regulatory agencies. These independent assessments can provide valuable insights and recommendations for improving the plan’s effectiveness.

Innovative Approaches to Farm Waste

The agricultural sector is constantly evolving, and with it, the strategies for managing farm waste. Innovation is key to minimizing environmental impact, improving efficiency, and potentially generating revenue. This section explores some of the cutting-edge technologies and approaches shaping the future of farm waste management.

Emerging Technologies and Approaches in Farm Waste Management

New technologies are transforming how farms handle waste, offering more sustainable and efficient solutions. These innovations address various aspects, from waste collection and processing to resource recovery.

- Precision Agriculture and Waste Monitoring: Precision agriculture techniques, utilizing sensors, drones, and GPS, are now being applied to waste management. These tools help farmers monitor waste generation in real-time, optimizing manure application and reducing runoff. For example, sensors can track nutrient levels in manure, allowing for precise application based on crop needs, minimizing the risk of over-fertilization and environmental pollution.

- Advanced Anaerobic Digestion: Beyond traditional anaerobic digestion, new technologies are emerging, such as two-stage digestion and co-digestion, where agricultural waste is processed with other organic materials like food waste. These methods increase biogas production efficiency and broaden the range of feedstocks that can be utilized.

- Automated Waste Sorting and Processing: Robotic systems and AI-powered sorting technologies are being developed to separate different waste streams more efficiently. This is especially beneficial for farms that produce a variety of waste types, facilitating the recovery of valuable materials for reuse or recycling.

- Bioreactors and Biofilters: These systems are employed to treat liquid waste and gaseous emissions. They use microorganisms to break down pollutants, reducing odors and mitigating environmental impacts. Some bioreactors are designed to simultaneously produce biogas.

- Closed-Loop Systems: These systems aim to minimize waste by reusing resources within the farm. Examples include using treated wastewater for irrigation or recovering nutrients from manure to produce fertilizers.

Waste-to-Energy Systems

Waste-to-energy (WTE) technologies offer a significant opportunity to transform farm waste into a valuable energy source. These systems not only reduce waste volume but also generate renewable energy, reducing reliance on fossil fuels.

- Anaerobic Digestion (AD): AD is a widely used WTE technology. It involves the breakdown of organic matter in the absence of oxygen, producing biogas (primarily methane and carbon dioxide). This biogas can be used to generate electricity, heat, or as a transportation fuel. The digestate, the byproduct of AD, is a nutrient-rich fertilizer. For example, a dairy farm in California utilizes AD to process manure, generating enough electricity to power its operations and sell excess energy back to the grid.

- Combustion and Incineration: While less common due to environmental concerns, combustion and incineration can be used to burn certain types of farm waste, such as crop residues, to produce heat and electricity. Modern incinerators are equipped with advanced emission control systems to minimize air pollution.

- Gasification: Gasification converts organic materials into a syngas (a mixture of carbon monoxide, hydrogen, and other gases) through partial oxidation at high temperatures. The syngas can then be used to generate electricity or as a feedstock for producing chemicals.

- Pyrolysis: Pyrolysis involves the thermal decomposition of organic materials in the absence of oxygen. It produces bio-oil, biochar, and syngas. Bio-oil can be used as a fuel, biochar can be used as a soil amendment, and syngas can be used to generate electricity.

Research Related to Innovative Waste Management Solutions

Ongoing research is critical for developing more efficient, sustainable, and cost-effective farm waste management solutions. These studies explore new technologies, optimize existing processes, and evaluate environmental impacts.

- Biochar Production and Application: Researchers are investigating the use of biochar, produced through pyrolysis, as a soil amendment. Biochar can improve soil fertility, water retention, and carbon sequestration. Studies are evaluating the optimal feedstock materials and application rates for different crops and soil types.

- Algae-Based Wastewater Treatment: Algae are being explored for their ability to remove nutrients from wastewater, such as nitrogen and phosphorus. The harvested algae biomass can then be used as a feedstock for biofuel production or as animal feed. Research is focused on optimizing algae growth conditions and developing efficient harvesting methods.

- Valorization of Digestate: Research is being conducted to improve the utilization of digestate, the byproduct of anaerobic digestion. This includes developing methods to concentrate nutrients, produce specialized fertilizers, and extract valuable compounds.

- Development of Novel Bioreactors: Scientists are working on designing innovative bioreactor systems that are more efficient, cost-effective, and adaptable to different types of farm waste. This includes exploring new microbial consortia and optimizing reactor configurations.

- Technological Advancements in Sensor and Data Analysis: Current research focuses on creating more sophisticated sensor systems to monitor waste production and composition in real time. These sensors, combined with advanced data analytics, enable farmers to make informed decisions about waste management practices, optimizing resource use and reducing environmental impact.

The Potential of Using AI in Farm Waste Management

Artificial intelligence (AI) has the potential to revolutionize farm waste management, offering data-driven insights and automation capabilities. AI can improve efficiency, reduce environmental impact, and optimize resource utilization.

- Predictive Analytics: AI algorithms can analyze historical data on waste generation, weather patterns, and crop yields to predict future waste production levels. This allows farmers to proactively plan waste management strategies, such as adjusting manure storage capacity or optimizing composting schedules.

- Optimization of Anaerobic Digestion: AI can be used to optimize the performance of anaerobic digestion systems. By analyzing data from sensors, AI can adjust parameters like feedstock composition, temperature, and pH levels to maximize biogas production efficiency.

- Automated Sorting and Processing: AI-powered robots can be used to sort and process farm waste, separating different waste streams for recycling, reuse, or energy generation. AI algorithms can be trained to identify and classify different types of waste based on their physical properties or chemical composition.

- Precision Manure Application: AI can integrate data from sensors, weather forecasts, and soil analysis to optimize manure application rates. This minimizes the risk of over-fertilization, reduces nutrient runoff, and improves crop yields.

- Real-time Monitoring and Decision Support: AI-powered dashboards can provide farmers with real-time insights into their waste management operations. This allows them to make informed decisions about waste handling, storage, and treatment, improving efficiency and reducing environmental impact. For example, an AI system could detect leaks in manure storage facilities, alerting farmers to potential environmental hazards.

Health and Safety Considerations

Managing farm waste effectively is not only about environmental sustainability and economic efficiency; it’s also fundamentally about safeguarding the health and safety of farm workers, the surrounding community, and the environment. Farm waste, if mishandled, can pose significant risks, ranging from immediate physical hazards to long-term health issues. Therefore, implementing robust health and safety protocols is paramount.

Potential Health Hazards Associated with Farm Waste

Farm waste streams contain a variety of materials that can present health hazards. Understanding these hazards is the first step in mitigating risks.

- Biological Hazards: Farm waste often harbors pathogens, including bacteria (e.g., E. coli, Salmonella), viruses, and parasites. These can cause illnesses such as gastroenteritis, respiratory infections, and zoonotic diseases transmissible from animals to humans. For example, improper handling of manure can lead to the spread of cryptosporidiosis, a parasitic infection causing severe diarrhea.

- Chemical Hazards: Pesticides, herbicides, fertilizers, and cleaning agents, often present in farm waste, can cause skin irritation, respiratory problems, and even long-term health effects such as cancer. Exposure can occur through direct contact, inhalation, or ingestion. The improper disposal of pesticide containers can contaminate soil and water sources, leading to chronic health issues.