Embarking on the journey of aquaculture? Understanding how to calculate fish feed conversion rate (FCR) is paramount for success. This crucial metric acts as a compass, guiding fish farmers toward efficient resource management and improved profitability. It’s more than just numbers; it’s a window into the health of your fish, the effectiveness of your feed, and the overall sustainability of your farming practices.

This guide aims to demystify FCR, providing you with the knowledge and tools to optimize your aquaculture operations.

From grasping the core concept of FCR and its significance in aquaculture to navigating the intricacies of data collection and interpretation, this comprehensive guide will walk you through every step. You will learn how to collect the right data, apply the correct formulas, and understand how environmental conditions, feed quality, and fish species influence the FCR values. Whether you are a seasoned aquaculturist or just starting, this information will help you make informed decisions and ensure a thriving fish farming venture.

Understanding Fish Feed Conversion Rate (FCR)

Fish Feed Conversion Rate (FCR) is a critical metric in aquaculture, reflecting the efficiency with which fish convert feed into body mass. Understanding and managing FCR is essential for optimizing production, minimizing costs, and ensuring the sustainability of fish farming operations.

Fundamental Concept of FCR in Aquaculture

FCR fundamentally quantifies the relationship between the amount of feed provided to fish and the amount of weight they gain. This ratio provides a direct measure of how effectively the fish are utilizing the feed to grow. A lower FCR indicates greater efficiency, meaning less feed is required to produce a given amount of fish biomass. Conversely, a higher FCR suggests that the fish are less efficient at converting feed into growth, potentially due to factors like feed quality, environmental conditions, or fish health.

Definition of FCR and Units of Measurement

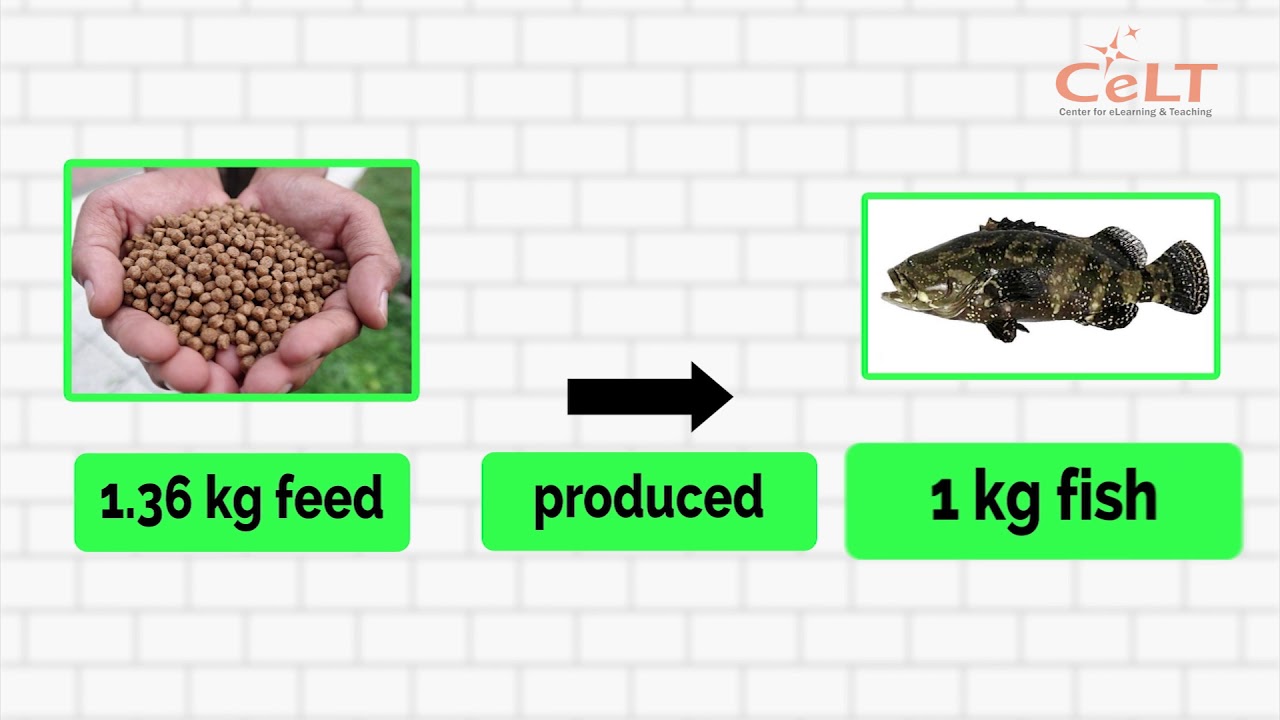

The Feed Conversion Rate (FCR) is defined as the mass of feed consumed divided by the mass of weight gained by the fish.

FCR = (Total Feed Consumed) / (Weight Gain)

The units of measurement for FCR are typically expressed as a ratio, such as kilograms of feed per kilogram of weight gain (kg feed/kg gain). Other common units include pounds of feed per pound of weight gain (lbs feed/lbs gain). The FCR value is always a dimensionless number, representing the efficiency of feed utilization. For example, an FCR of 1.5 indicates that 1.5 kilograms of feed were required to produce 1 kilogram of fish weight gain.

Significance of FCR in Assessing Fish Farming Efficiency

FCR serves as a key performance indicator (KPI) for assessing the economic and environmental efficiency of fish farming. Monitoring and optimizing FCR can significantly impact profitability and sustainability.

- Cost Control: Feed often represents the largest operational expense in aquaculture. A lower FCR directly translates to reduced feed costs per unit of fish produced, thereby increasing profit margins.

- Production Efficiency: FCR provides insights into the overall efficiency of the farming operation. A well-managed farm typically exhibits a lower FCR, indicating optimal feeding practices, water quality, and fish health.

- Environmental Impact: Excess feed contributes to water pollution through uneaten feed and fish waste. A lower FCR minimizes feed waste, reducing the environmental footprint of the aquaculture operation.

- Resource Management: Efficient feed utilization contributes to sustainable aquaculture practices by conserving resources and minimizing waste. This aligns with the growing demand for environmentally responsible food production.

Factors Influencing FCR

Several factors can influence the FCR in aquaculture, impacting the efficiency of feed utilization. Understanding these factors is crucial for implementing effective management strategies.

- Feed Quality and Composition: The nutritional content of the feed, including the balance of protein, carbohydrates, fats, vitamins, and minerals, significantly affects FCR. High-quality feed formulated to meet the specific nutritional needs of the fish species will generally result in a lower FCR. For example, feed with the appropriate protein content for the growth stage of the fish is critical.

- Fish Species and Genetics: Different fish species have varying metabolic rates and growth potentials, leading to differences in FCR. Selective breeding programs can improve the genetic traits related to feed efficiency, resulting in lower FCRs. For example, fast-growing strains of salmon often exhibit better FCRs compared to slower-growing strains.

- Fish Size and Age: FCR often changes as fish grow. Younger fish typically have higher growth rates and more efficient feed conversion. As fish mature, their growth rate slows, and the FCR tends to increase.

- Environmental Conditions: Water quality parameters, such as temperature, dissolved oxygen, and pH, significantly impact fish metabolism and feed utilization. Optimal water quality promotes efficient feed conversion, while poor water quality can stress fish and reduce their ability to convert feed effectively.

- Feeding Practices: The frequency, timing, and method of feeding can influence FCR. Overfeeding or underfeeding can both negatively affect FCR. Proper feed management, including accurate feed allocation and observation of feeding behavior, is essential for optimizing FCR.

- Fish Health: Diseases and parasites can impair fish health, reducing their ability to utilize feed efficiently. Healthy fish typically exhibit lower FCRs. Proactive disease prevention and management are crucial for maintaining optimal FCR.

Data Collection and Calculation Basics

To accurately determine the efficiency of fish feed, meticulous data collection is essential. This section details the necessary data points, the calculation formula, and the organization of the data collection process. Precise record-keeping ensures that informed decisions can be made to optimize fish farming practices.

Data Points Required to Calculate FCR

Several key data points are crucial for calculating the Fish Feed Conversion Rate (FCR). These values provide the foundation for understanding how effectively feed is being utilized by the fish.

- Initial Fish Weight: The total weight of the fish at the beginning of the feeding trial or observation period. This establishes a baseline for comparison.

- Final Fish Weight: The total weight of the fish at the end of the feeding trial or observation period. This allows for the calculation of weight gain.

- Total Feed Consumed: The total amount of feed provided to the fish during the feeding trial or observation period. This is measured in units like kilograms or pounds.

- Mortality (if any): The number of fish that died during the observation period, along with their individual or total weight. This is important for adjusting calculations to reflect actual biomass gain.

Formula for Calculating FCR

The Fish Feed Conversion Rate (FCR) is calculated using a straightforward formula. This formula helps quantify the relationship between feed input and fish weight gain.

FCR = Total Feed Consumed / Net Weight Gain

Here’s a breakdown of each component:

- Total Feed Consumed: As previously mentioned, this is the total weight of the feed provided to the fish over the specified period.

- Net Weight Gain: This represents the increase in the total weight of the fish. It’s calculated as:

Net Weight Gain = Final Fish Weight – Initial Fish Weight – Weight of Dead Fish (if any)

- The FCR value indicates how many units of feed are required to produce one unit of fish weight gain. For example, an FCR of 1.5 means that 1.5 kilograms of feed are needed to produce 1 kilogram of fish.

Organizing the Data Collection Process

A well-organized data collection process is critical for accurate FCR calculations. Consistent and systematic data collection minimizes errors and ensures reliable results.

- Frequency of Weighing: The frequency of weighing depends on the fish species, growth rate, and the duration of the study. Regular weighing, such as weekly or bi-weekly, is recommended to monitor growth and feed efficiency. More frequent weighing is often necessary during periods of rapid growth.

- Method of Weighing Fish: Use accurate weighing scales. For small fish, a representative sample can be weighed. For larger fish, the entire population should be weighed, if possible. Ensure the weighing process minimizes stress on the fish.

- Method of Measuring Feed: Precisely measure the amount of feed provided. Use calibrated containers or scales to measure the feed accurately. Keep records of the feed type, batch number, and any changes in feed.

- Duration of the Trial: The duration of the data collection period depends on the fish species, the goals of the study, and the time required to observe significant changes in growth and feed conversion. A longer period usually provides more reliable data.

Sample Data Table and Calculation

The following table presents a sample dataset illustrating how to calculate FCR. This example demonstrates the application of the formula using hypothetical values. The table uses a responsive design, adapting to different screen sizes for optimal readability.

| Fish Weight Gain (kg) | Feed Consumed (kg) | Mortality (kg) | FCR |

|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 150 | 5 | 1.55 |

| 120 | 180 | 0 | 1.50 |

| 80 | 100 | 2 | 1.27 |

In the first row, the FCR is calculated as: FCR = 150 kg / (100 kg – 5 kg) = 1.55. This means that for every 1 kg of fish gained, 1.55 kg of feed was consumed. The table illustrates how the FCR can vary based on factors like fish growth and feed efficiency.

Methods for Calculating FCR

Calculating Fish Feed Conversion Rate (FCR) is a fundamental practice in aquaculture, offering crucial insights into the efficiency of feed utilization. Accurate FCR calculations are essential for optimizing feeding strategies, managing costs, and ensuring sustainable fish farming practices. This section provides a detailed, step-by-step guide to calculating FCR, including a practical example and considerations for data accuracy.

Step-by-Step Procedure for Calculating FCR

The calculation of FCR involves a straightforward process that requires accurate data collection. Here’s a detailed breakdown of the steps involved:

- Weigh the Fish at the Beginning of the Period: Accurately measure the total weight of the fish population at the start of the designated period (e.g., weekly, monthly, or the entire grow-out cycle). This provides the baseline weight for comparison.

- Weigh the Fish at the End of the Period: At the end of the period, measure the total weight of the fish population again. This includes any weight gain achieved during the period.

- Calculate the Total Weight Gain: Subtract the initial weight from the final weight to determine the total weight gain of the fish.

- Measure the Total Feed Consumption: Accurately record the total amount of feed (in kilograms or pounds) consumed by the fish during the same period. This is a critical component of the FCR calculation.

- Calculate FCR: Divide the total feed consumption by the total weight gain. The formula is as follows:

FCR = Total Feed Consumed / Total Weight Gain

Practical Example with Realistic Values

Let’s illustrate the FCR calculation with a practical example using realistic values for tilapia farming:Suppose a farmer has a pond of tilapia.

- Initial Fish Weight: At the beginning of a month, the total weight of the tilapia in the pond is 1,000 kg.

- Final Fish Weight: At the end of the month, the total weight of the tilapia is 1,500 kg.

- Total Weight Gain: The total weight gain is 1,500 kg – 1,000 kg = 500 kg.

- Total Feed Consumption: During the month, the tilapia consumed 750 kg of feed.

- FCR Calculation: The FCR is calculated as 750 kg / 500 kg = 1.5.

This means that for every 1.5 kg of feed consumed, the tilapia gained 1 kg of weight. A lower FCR generally indicates better feed efficiency.

Potential Errors and Mitigation Strategies

Accurate data collection is essential for reliable FCR calculations. Several potential errors can occur during data collection, and it’s important to implement mitigation strategies to minimize these errors.

- Inaccurate Weighing: Using inaccurate scales or improper weighing techniques can lead to errors.

- Mitigation: Calibrate scales regularly, use appropriate weighing equipment (e.g., a digital scale with sufficient capacity and accuracy for the fish size), and ensure proper weighing procedures are followed. Weigh fish in a net or container that has been tared to zero.

- Inaccurate Feed Measurement: Incorrectly measuring the amount of feed dispensed can skew the FCR.

- Mitigation: Use calibrated measuring devices (e.g., feed scoops, weighing scales for feed) and maintain accurate records of feed dispensed. Monitor feed wastage and adjust feeding practices to minimize loss.

- Mortality: Fish mortality during the period will affect the accuracy of the calculation if not accounted for.

- Mitigation: Record and account for any fish mortality. If possible, weigh dead fish to estimate the loss of biomass. Adjust the final weight accordingly.

- Variations in Feed Quality: Using feed with inconsistent nutritional content will impact growth and FCR.

- Mitigation: Purchase feed from reputable suppliers with consistent quality control. Regularly analyze feed samples to ensure nutritional specifications are met.

- Incomplete Data Records: Missing data or incomplete records will make the FCR calculation unreliable.

- Mitigation: Establish a detailed record-keeping system. Train staff on proper data collection procedures. Regularly review and verify the accuracy of all data entries.

Flow Chart Representing the FCR Calculation Process

A flowchart provides a visual representation of the FCR calculation process.[A flowchart would be represented here. The flowchart begins with “Start” and moves to “Weigh Fish (Initial)”. From there, it branches to “Measure Feed Consumed”. The next steps are “Weigh Fish (Final)”, “Calculate Weight Gain (Final – Initial)”, and finally “Calculate FCR (Feed Consumed / Weight Gain)”. The flowchart ends with “End”.

The chart is simple and linear, showing the sequence of steps.]The flowchart visually summarizes the steps involved, from initial fish weighing to the final FCR calculation, aiding in understanding and ensuring all necessary steps are included in the process.

Interpreting FCR Results

Understanding the Fish Feed Conversion Rate (FCR) is only the first step. The real value comes from interpreting the results and using them to improve aquaculture practices. This section will guide you through understanding different FCR values, establishing benchmarks, optimizing feeding strategies, and recognizing the impact of FCR on profitability and sustainability.

Understanding FCR Values

Interpreting FCR values requires understanding what the numbers represent. A lower FCR is always better, indicating that the fish are converting feed into biomass more efficiently. A higher FCR suggests the opposite, that is, a significant portion of the feed is not being converted into fish growth. This can be due to several factors, including feed quality, environmental conditions, and fish health.For example:

An FCR of 1.0 means that for every 1 kilogram of feed given, the fish gained 1 kilogram of weight.

An FCR of 2.0 means that the fish gained 1 kilogram of weight for every 2 kilograms of feed given.

The difference in these examples shows the significance of the FCR value.

Acceptable FCR Benchmarks

Acceptable FCR values vary greatly depending on the fish species, the production system, and the specific goals of the farm. Establishing benchmarks or reference ranges is crucial for evaluating performance and identifying areas for improvement.Here are some general reference ranges for common aquaculture species:

- Tilapia: Generally, a good FCR for tilapia ranges from 1.2 to 1.8. Well-managed farms may achieve FCRs closer to 1.2, especially with high-quality feed and optimal environmental conditions.

- Salmon: Salmon often have higher FCRs due to their carnivorous nature. An FCR of 1.1 to 1.4 is considered good for salmon farming.

- Catfish: Catfish typically have FCRs between 1.5 and 2.0. Efficient farms with good feed management can achieve FCRs closer to 1.5.

- Shrimp: Shrimp FCRs can vary, but a value between 1.4 and 1.8 is generally acceptable. Factors such as shrimp species and farming practices significantly influence this value.

These ranges serve as a starting point, and specific farm conditions and production goals should be considered when setting targets.

Optimizing Fish Feeding Strategies

Analyzing FCR results is a powerful tool for optimizing fish feeding strategies. By tracking FCR over time and correlating it with feeding practices, farmers can identify areas where improvements can be made.The following actions can be used to optimize feeding strategies:

- Feed Quality Assessment: If the FCR is poor, the first step is to evaluate the feed’s nutritional content, digestibility, and palatability. Switching to a higher-quality feed or adjusting the feed formulation may improve FCR.

- Feeding Rate Adjustments: Overfeeding can lead to poor FCR because uneaten feed pollutes the water and reduces the fish’s ability to consume feed efficiently. Adjusting feeding rates based on fish size, water temperature, and feeding behavior is crucial.

- Feeding Frequency: Increasing the feeding frequency, especially for young fish, can improve FCR by providing a more consistent supply of nutrients.

- Monitoring Fish Health: Healthy fish convert feed more efficiently. Regular health checks and disease prevention measures are essential for maintaining a good FCR.

- Environmental Management: Maintaining optimal water quality parameters, such as temperature, dissolved oxygen, and pH, supports fish health and growth, thus improving FCR.

Impact of Poor FCR

Poor FCR has significant implications for both profitability and sustainability in aquaculture. A high FCR means that more feed is required to produce the same amount of fish, leading to increased feed costs, which are a major expense in aquaculture operations. Additionally, poor FCR can contribute to environmental problems.Here’s a summary of the impact of poor FCR:

- Reduced Profitability: Higher feed costs directly reduce profit margins. Farms with poor FCRs are less competitive and may struggle to remain profitable.

- Increased Environmental Impact: Uneaten feed decomposes in the water, leading to increased organic waste, which can degrade water quality, cause algal blooms, and deplete oxygen levels. This can negatively impact the health of the fish and the surrounding ecosystem.

- Sustainability Concerns: The overconsumption of feed and its inefficient conversion into biomass contributes to the overexploitation of marine resources used in fish feed, raising sustainability concerns.

- Increased Risk of Disease: Poor water quality resulting from excess feed can stress fish, making them more susceptible to disease outbreaks, which can further reduce productivity and increase costs.

Factors Affecting FCR

The quality and formulation of fish feed are critical determinants of Feed Conversion Rate (FCR). The composition of the feed directly impacts how efficiently fish utilize the nutrients provided. Understanding these factors allows aquaculturists to optimize feeding strategies, minimize waste, and improve profitability.

Feed Quality and FCR

Feed quality significantly influences FCR. High-quality feed provides essential nutrients in a readily digestible form, promoting efficient growth and reducing waste. Poor-quality feed, on the other hand, can lead to reduced nutrient absorption, increased waste production, and a higher FCR.

- Protein Content and FCR: Protein is essential for fish growth. The protein content of the feed directly impacts FCR. Higher protein levels, within optimal ranges, generally lead to better FCR. However, excessive protein can lead to increased waste, as fish cannot utilize all the excess protein, resulting in higher FCR. For example, a study on Nile tilapia found that a feed with 32% protein resulted in a better FCR than a feed with 28% or 36% protein, demonstrating an optimal protein level.

- Digestibility and FCR: The digestibility of the feed components is crucial. Digestible ingredients are more easily broken down and absorbed by the fish, leading to better nutrient utilization and a lower FCR. Ingredients with high digestibility, such as fish meal, are preferred over those with lower digestibility, such as certain plant-based proteins, as they contribute to better FCR.

Feed Formulations and FCR

Different feed formulations can have varying effects on FCR. The balance of nutrients, the inclusion of specific ingredients, and the physical characteristics of the feed all play a role. Formulations are often tailored to the species and life stage of the fish.

- Balanced Nutrient Ratios: A well-balanced feed provides the correct ratios of protein, carbohydrates, fats, vitamins, and minerals. An imbalance can lead to inefficient nutrient utilization and a higher FCR. For example, a feed deficient in essential amino acids will limit protein synthesis and increase FCR, even if the protein content is adequate.

- Ingredient Selection: The choice of ingredients significantly impacts FCR. Using high-quality ingredients with high digestibility and optimal nutrient profiles is essential. For instance, incorporating fish oil as a fat source often leads to better FCR compared to using vegetable oils, particularly for marine fish.

- Feed Processing: The way feed is processed (e.g., extrusion, pelleting) can influence its physical properties and digestibility. Extruded feeds are often more digestible than non-extruded feeds, resulting in better FCR.

Common Feed Ingredients and FCR Contribution

Various ingredients are used in fish feed, each contributing differently to FCR. Understanding the role of each ingredient helps in formulating effective and cost-efficient diets.

- Fish Meal: Fish meal is a highly digestible protein source and contributes significantly to lower FCR. It provides essential amino acids and is readily utilized by fish.

- Soybean Meal: Soybean meal is a plant-based protein source that can be used as a substitute for fish meal. However, its digestibility may be lower, potentially leading to a slightly higher FCR compared to fish meal, depending on the processing and inclusion of other ingredients.

- Cereals (e.g., Corn, Wheat): Cereals provide carbohydrates for energy. They can influence FCR depending on their digestibility and inclusion levels. Overuse can lead to reduced protein utilization.

- Fish Oil: Fish oil is a good source of essential fatty acids. It typically leads to improved FCR, especially for marine fish species, by improving growth and nutrient utilization.

- Vitamins and Minerals: Vitamins and minerals are essential for various physiological functions. Deficiencies can negatively affect growth and FCR.

Selecting Appropriate Feed for Fish Species and Life Stages

The choice of feed must be tailored to the specific fish species and its life stage. Different species have different nutritional requirements, and these requirements change as the fish grows.

- Species-Specific Requirements: Different fish species have varying requirements for protein, fats, and other nutrients. For example, carnivorous fish, such as salmon, require higher protein levels than herbivorous fish, such as carp.

- Life Stage-Specific Requirements: The nutritional needs of fish change throughout their life cycle. Fry (young fish) require high-protein diets for rapid growth. As fish mature, the protein requirements decrease, and the need for energy from carbohydrates and fats increases.

- Example: A feed formulation for larval Atlantic salmon (fry) would typically contain a high protein content (e.g., 50-60%) to support rapid growth, while a feed for adult Atlantic salmon would have a lower protein content (e.g., 40-45%) and a higher fat content to support growth and energy storage for reproduction.

- Feed Size and Format: The size and format of the feed (e.g., crumble, pellet) must be appropriate for the size and feeding behavior of the fish. Fry require small, easily digestible crumbles, while larger fish can consume larger pellets.

Factors Affecting FCR

Environmental conditions significantly impact fish feed conversion rate (FCR). Maintaining optimal environmental parameters is crucial for efficient feed utilization and overall fish health. This section will explore the influence of water temperature, water quality, and stocking density on FCR in aquaculture systems.

Water Temperature Effects on FCR

Water temperature directly influences a fish’s metabolism and, consequently, its FCR. Fish are ectothermic, meaning their body temperature is regulated by the surrounding water. Temperature fluctuations affect their appetite, digestion, and the rate at which they convert feed into body mass.* Optimal Temperature Ranges: Different fish species have specific temperature ranges where they exhibit optimal growth and feed conversion efficiency.

For example, trout thrive in cooler waters, while tilapia prefer warmer temperatures. Maintaining the appropriate temperature range is vital for minimizing FCR.

Impact of Low Temperatures

At low temperatures, fish metabolism slows down, leading to reduced appetite and slower growth rates. This can result in a higher FCR, as the fish consumes feed but doesn’t efficiently convert it into biomass. The fish may also expend more energy to maintain basic bodily functions, further reducing feed efficiency.

Impact of High Temperatures

Conversely, excessively high temperatures can stress fish, reducing their appetite and increasing their metabolic rate. This can lead to inefficient feed utilization and increased FCR. Moreover, higher temperatures often coincide with lower dissolved oxygen levels, exacerbating stress and negatively impacting growth.

Example

Consider a study on rainbow trout. Researchers found that at 10°C, the FCR was significantly higher compared to 15°C or 20°C. This demonstrates the direct correlation between temperature and feed conversion efficiency.

Influence of Water Quality Parameters on FCR

Water quality encompasses various parameters, including dissolved oxygen, pH, ammonia, nitrite, and salinity. These parameters play a crucial role in fish health and their ability to efficiently utilize feed. Poor water quality can stress fish, leading to decreased appetite, impaired digestion, and increased susceptibility to diseases, all of which negatively affect FCR.* Dissolved Oxygen (DO): Adequate DO levels are essential for fish respiration and metabolic processes.

Low DO levels stress fish, reducing their feed intake and growth. This leads to a higher FCR.

pH

Optimal pH levels (typically between 6.5 and 9.0) are necessary for maintaining fish health and the efficiency of biological processes. Extreme pH values can stress fish, hindering their ability to digest feed and utilize nutrients effectively, thus increasing FCR.

Ammonia and Nitrite

These are toxic byproducts of fish metabolism and uneaten feed decomposition. Elevated levels of ammonia and nitrite can damage fish gills, impair oxygen uptake, and reduce feed intake. The fish may allocate energy to detoxifying their system, leading to a higher FCR.

Salinity

Salinity impacts the osmoregulation of fish. Inappropriate salinity levels can stress fish, affecting their ability to absorb nutrients and maintain energy balance, which results in poor feed conversion.

Example

In a study on shrimp farming, it was observed that shrimp exposed to high levels of ammonia had a significantly higher FCR compared to shrimp in tanks with well-managed water quality.

Relationship Between Stocking Density and FCR

Stocking density refers to the number of fish per unit volume of water. While increasing stocking density can maximize production, it also affects water quality and fish health, which, in turn, impacts FCR.* Low Stocking Density: At low stocking densities, fish have more space to move and access resources. This often leads to better feed conversion efficiency because the fish are less stressed and have better access to feed.

However, low densities may not be economically viable due to lower overall production.

High Stocking Density

High stocking densities can lead to overcrowding, increased competition for food, and a build-up of waste products, such as ammonia and nitrite. These factors can stress fish, decrease their appetite, and increase the risk of disease outbreaks. This, in turn, leads to a higher FCR.

Impact on Water Quality

High stocking densities accelerate the deterioration of water quality. Uneaten feed and fish waste accumulate, leading to a decline in dissolved oxygen and an increase in toxic metabolites, further impacting FCR.

Example

Research on salmon farming has shown that at higher stocking densities, FCR tends to increase due to the combined effects of reduced water quality and increased stress. Farmers often try to find the optimal stocking density to balance productivity and maintain acceptable FCR levels.

Comparison of Environmental Conditions and Their Effect on FCR

The following table summarizes the impact of various environmental conditions on FCR:

| Environmental Factor | Optimal Conditions | Effect on FCR | Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Water Temperature | Species-specific optimal range (e.g., 15-20°C for trout) | Low FCR | Promotes efficient metabolism, digestion, and growth. |

| Dissolved Oxygen | High levels (e.g., >5 mg/L) | Low FCR | Ensures efficient respiration and metabolic processes. |

| pH | Optimal range (e.g., 6.5-9.0) | Low FCR | Maintains fish health and facilitates biological processes. |

| Ammonia/Nitrite | Low levels (e.g., <0.02 mg/L ammonia) | Low FCR | Prevents toxicity and stress, promoting feed intake. |

| Stocking Density | Optimal density (species-specific) | Low FCR | Balances production with water quality and fish health. |

Factors Affecting FCR

The Feed Conversion Rate (FCR) is a crucial metric in aquaculture, reflecting the efficiency with which fish convert feed into body mass. Several factors influence FCR, impacting the profitability and sustainability of fish farming. Understanding these factors allows farmers to optimize feeding strategies and improve production efficiency.

Fish Species and Genetics

Different fish species exhibit varying FCR values due to differences in their physiology, metabolism, and feeding habits. These variations directly impact the efficiency with which they utilize feed.

- Species-Specific FCR Variation: Fish species have inherent differences in their ability to convert feed into biomass. Some species are naturally more efficient converters than others.

- Examples of FCR Values:

- Good FCR (typically below 1.5): Species like tilapia, channel catfish, and carp often exhibit relatively good FCRs. For instance, well-managed tilapia farms can achieve FCRs close to 1.2-1.4.

- Poor FCR (typically above 2.0): Marine fish, such as certain species of tuna or salmon, often have poorer FCRs. The FCR for Atlantic salmon can range from 1.2 to 1.8, depending on factors like diet, environment, and genetics. Some predatory species, with higher protein requirements, may have FCRs exceeding 2.0.

Genetics play a significant role in determining an individual fish’s potential FCR. Selective breeding programs can enhance the efficiency of feed utilization within a species.

- Genetic Influence on FCR: Breeding programs can select for fish with traits that promote efficient feed conversion, such as faster growth rates, improved feed digestion, and reduced energy expenditure.

- Selective Breeding Examples:

- Tilapia Breeding: Selective breeding has been used to develop faster-growing tilapia strains with improved FCRs, allowing for increased production within the same timeframe.

- Salmon Breeding: Breeding programs in salmon have focused on improving growth rates, disease resistance, and feed efficiency, resulting in lower FCRs and increased yields.

The choice of fish species and the genetic makeup of the stock significantly impact FCR. Species with inherently better feed conversion abilities, combined with selective breeding efforts, can dramatically improve the economic viability and environmental sustainability of aquaculture operations. Farmers should carefully consider species selection and genetic improvement strategies to optimize FCR and maximize profitability.

Monitoring and Improving FCR

Regular monitoring and consistent improvement efforts are crucial for maximizing profitability and sustainability in aquaculture. Implementing effective strategies for tracking and enhancing Fish Feed Conversion Rate (FCR) requires a proactive approach, combining meticulous data collection, insightful analysis, and adaptive management practices. This section details the best practices for monitoring FCR, strategies for improvement, and actionable tips for fish farmers.

Regular FCR Monitoring Practices

Consistent monitoring of FCR is essential for identifying trends, detecting problems, and evaluating the effectiveness of management strategies. This involves establishing a structured system for data collection and analysis.

- Establish a Consistent Data Collection Schedule: Implementing a regular schedule for weighing fish and measuring feed input is crucial. The frequency of data collection should be determined by the fish species, growth rate, and the specific farming system. For example, in intensive farming systems with rapidly growing species like tilapia or catfish, weekly or bi-weekly monitoring might be appropriate. In extensive systems or with slower-growing species, monthly monitoring could be sufficient.

- Maintain Accurate Records: Accurate record-keeping is the cornerstone of effective FCR monitoring. Detailed records should include the date, the weight of fish sampled, the total feed provided, and any observations about fish health or environmental conditions. Utilize a standardized data entry format to minimize errors and facilitate analysis. Consider using spreadsheets or specialized aquaculture management software to streamline the process.

- Implement Regular Sampling: Sample a representative number of fish from the population to obtain accurate weight measurements. The number of fish sampled should be based on the size of the population and the desired level of accuracy. A larger sample size will generally provide a more reliable estimate of the average fish weight and, consequently, the FCR.

- Utilize Appropriate Weighing Scales: Ensure the use of calibrated and accurate weighing scales for both fish and feed. The scales should be appropriate for the size and weight of the fish being weighed. Regular calibration of the scales is vital to maintain accuracy and avoid errors in FCR calculations.

- Analyze Data and Identify Trends: Analyze the collected data regularly to calculate FCR and identify any trends or anomalies. Compare the current FCR values with previous values to assess performance and detect any deviations from the expected range. Graphical representations of the data can help visualize trends and make it easier to identify potential issues.

Strategies for FCR Improvement

Improving FCR requires a multifaceted approach, focusing on optimizing feeding practices, feed quality, and environmental conditions. These strategies are designed to minimize feed wastage and maximize the efficiency with which fish convert feed into biomass.

- Optimize Feeding Schedules: Adjusting the feeding frequency and the amount of feed provided based on the fish’s age, size, and environmental conditions can significantly improve FCR. Consider the following:

- Feeding Frequency: Increase the feeding frequency for young, fast-growing fish, and reduce it as they mature. Multiple small feedings throughout the day are often more effective than fewer large feedings.

- Feeding Rate: Calculate the appropriate feeding rate based on the fish’s body weight and the feed’s nutritional content. Overfeeding leads to feed wastage, while underfeeding limits growth.

- Feeding Time: Feed fish during the periods when they are most active and have the best appetite. Avoid feeding during times of low oxygen levels or extreme temperatures.

- Enhance Feed Quality: Selecting high-quality feed with the appropriate nutritional profile is essential for optimal growth and FCR. The feed should be formulated to meet the specific nutritional requirements of the fish species and life stage. Consider the following:

- Protein Content: Ensure the feed contains an adequate amount of high-quality protein, which is essential for growth. The protein requirement varies depending on the fish species and life stage.

- Digestibility: Choose feed ingredients that are highly digestible to maximize nutrient absorption and minimize waste.

- Feed Formulation: Evaluate the feed formulation, including the ingredients used and the processing methods. Consider the use of specialized feeds designed to improve FCR.

- Manage Environmental Conditions: Maintaining optimal water quality and environmental conditions is crucial for fish health and growth, which directly impacts FCR.

- Water Quality: Monitor and maintain optimal water quality parameters, including dissolved oxygen, pH, ammonia, and nitrite levels. Poor water quality can stress fish and reduce their appetite, leading to poor FCR.

- Temperature: Maintain the appropriate water temperature for the fish species. Temperature affects the fish’s metabolism and growth rate.

- Stocking Density: Avoid overcrowding, which can lead to stress, disease, and poor FCR. Adjust stocking density based on the species, size, and the capacity of the farming system.

- Control Diseases and Parasites: Implementing effective disease prevention and control measures is critical for maintaining fish health and growth. Disease outbreaks can lead to reduced appetite, impaired nutrient absorption, and increased mortality, all of which negatively impact FCR.

- Biosecurity: Implement strict biosecurity measures to prevent the introduction and spread of diseases.

- Vaccination: Consider vaccinating fish against common diseases.

- Early Detection and Treatment: Monitor fish for signs of disease and parasites, and provide prompt treatment when necessary.

The Role of Feed Management in Enhancing FCR

Effective feed management is the cornerstone of improving FCR. This involves a holistic approach to feed selection, storage, delivery, and waste management. The goal is to maximize the utilization of feed nutrients by the fish.

- Feed Selection: Choose feeds that are specifically formulated for the fish species, life stage, and farming system. Consider the protein content, digestibility, and ingredient quality.

- Feed Storage: Store feed in a cool, dry place to prevent spoilage and nutrient degradation. Properly stored feed maintains its nutritional value and palatability.

- Feed Delivery: Use appropriate feeding methods, such as automatic feeders or hand feeding, to ensure accurate feed delivery and minimize waste.

- Waste Management: Implement strategies to minimize feed waste, such as adjusting feeding rates and using feed attractants.

- Regular Feed Evaluation: Regularly evaluate the feed’s performance by monitoring fish growth, FCR, and overall health.

Actionable Tips for Fish Farmers

Fish farmers can take several practical steps to improve their FCR values and enhance the profitability of their operations.

- Conduct Regular Water Quality Tests: Regularly monitor water quality parameters, such as dissolved oxygen, pH, ammonia, and nitrite levels.

- Adjust Feeding Rates Based on Fish Size: Adjust feeding rates based on the fish’s weight and growth stage to avoid overfeeding or underfeeding.

- Monitor Fish Health Regularly: Regularly inspect fish for signs of disease or parasites.

- Observe Feeding Behavior: Observe the fish’s feeding behavior to ensure they are consuming the feed effectively.

- Consider Feed Additives: Explore the use of feed additives, such as probiotics or enzymes, to improve digestion and nutrient absorption.

- Consult with Aquaculture Experts: Seek advice from aquaculture experts or nutritionists to optimize feeding strategies and improve FCR.

- Maintain Detailed Records: Keep meticulous records of feed input, fish weight, and environmental conditions.

- Benchmark Against Industry Standards: Compare FCR values with industry benchmarks to assess performance and identify areas for improvement.

Advanced FCR Concepts: Feed Efficiency Ratio (FER) and Protein Efficiency Ratio (PER)

Beyond the basic Feed Conversion Rate (FCR), understanding more nuanced metrics can provide a deeper insight into feed performance and fish growth. This section explores two such metrics: the Feed Efficiency Ratio (FER) and the Protein Efficiency Ratio (PER). These ratios offer alternative perspectives on how effectively fish utilize feed and protein, allowing for more informed decisions in aquaculture management.

Feed Efficiency Ratio (FER)

The Feed Efficiency Ratio (FER) provides a different perspective on feed utilization compared to FCR. While FCR focuses on the amount of feed needed to produce a unit of fish biomass, FER looks at the efficiency with which feed is converted into biomass. It’s essentially the inverse of FCR.The relationship between FCR and FER can be summarized as follows:

- FER = 1 / FCR

- FCR = 1 / FER

The higher the FER, the more efficient the feed is in converting to fish biomass.

Protein Efficiency Ratio (PER)

The Protein Efficiency Ratio (PER) is a critical metric, particularly for assessing the effectiveness of protein utilization in fish feed. Protein is a vital nutrient for fish growth, and the PER quantifies how efficiently the protein in the feed is converted into fish biomass. This ratio helps in evaluating the quality and digestibility of the protein source used in the feed.The formula for calculating PER is:

PER = (Weight Gain of Fish) / (Protein Intake)

To calculate PER:

- Determine the Weight Gain of Fish: This is the difference between the final weight and the initial weight of the fish over a specific period. Ensure that the weight is measured consistently, using the same scale and methodology.

- Determine Protein Intake: This involves calculating the total amount of protein consumed by the fish during the same period. This requires knowing the amount of feed consumed and the protein percentage in the feed. For example, if the fish consumed 100 kg of feed with a 30% protein content, the protein intake would be 30 kg (100 kg – 0.30).

- Calculate PER: Divide the weight gain of the fish by the protein intake. For instance, if the fish gained 15 kg and consumed 30 kg of protein, the PER would be 0.5 (15 kg / 30 kg).

A higher PER indicates that the protein in the feed is being utilized more effectively for growth.

Comparing FCR, FER, and PER

Understanding the distinctions between FCR, FER, and PER is essential for a comprehensive assessment of feed performance.

| Metric | Formula | Focus | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| FCR | Feed Consumed / Weight Gain | Feed Efficiency (inverse) | Lower FCR is better. Indicates less feed is needed to produce a unit of fish biomass. |

| FER | Weight Gain / Feed Consumed | Feed Efficiency | Higher FER is better. Indicates more fish biomass is produced per unit of feed consumed. |

| PER | Weight Gain / Protein Intake | Protein Utilization Efficiency | Higher PER is better. Indicates more efficient use of dietary protein for fish growth. |

- Similarities: All three metrics are used to evaluate feed performance and fish growth efficiency. They all involve measurements of feed intake and weight gain.

- Differences: FCR and FER measure overall feed efficiency, while PER specifically focuses on protein utilization. FCR and FER are inversely related.

Using FER and PER to Evaluate Feed Performance

FER and PER provide valuable insights for evaluating feed performance.

- FER for Feed Comparison: Comparing the FER values of different feed formulations allows for the direct comparison of their overall efficiency. A feed with a higher FER is generally more cost-effective because it produces more fish biomass per unit of feed. For example, if Feed A has an FER of 0.7 and Feed B has an FER of 0.6, Feed A is more efficient.

- PER for Protein Source Evaluation: PER is particularly useful for evaluating the quality of protein sources in the feed. A higher PER suggests that the protein source is more digestible and contains a better amino acid profile, leading to more efficient growth. For instance, if a feed using fishmeal as the protein source yields a PER of 2.5, while a feed using soybean meal yields a PER of 2.0, fishmeal is a better protein source.

- Monitoring and Optimization: Tracking FER and PER over time can help identify trends and areas for improvement in feed management. This allows for optimizing feed formulations, feeding strategies, and overall aquaculture practices to maximize fish growth and minimize feed costs.

Case Studies: Real-World Examples of FCR in Aquaculture

Understanding how FCR functions in theory is essential, but seeing it applied in practice offers invaluable insights. Examining real-world case studies allows us to appreciate the complexities of FCR management, the factors influencing it, and the strategies employed to achieve optimal results. These examples demonstrate both successes and challenges, providing valuable lessons for aquaculturists.

Successful Fish Farm: Achieving Excellent FCR Values

A prime example of successful FCR management can be observed at a large-scale tilapia farm in Thailand. This farm consistently achieves FCR values below 1.2, a benchmark of excellent efficiency in tilapia aquaculture. Their success is rooted in a multifaceted approach.

- High-Quality Feed: The farm utilizes a commercially produced, extruded feed specifically formulated for tilapia. The feed has a high protein content (around 32%) and is supplemented with essential vitamins and minerals. The feed’s digestibility is also optimized.

- Optimized Feeding Regimen: The feeding schedule is carefully calibrated based on the fish’s age, size, and water temperature. Fish are fed multiple times a day, with the feeding rate adjusted based on regular monitoring of feed consumption and fish growth.

- Water Quality Management: Maintaining optimal water quality is a priority. The farm uses a combination of aeration, filtration, and regular water changes to ensure dissolved oxygen levels are high and ammonia and nitrite levels are low. Regular water quality testing is conducted.

- Health Management: Proactive health management is crucial. The farm implements strict biosecurity measures to prevent disease outbreaks. Fish are regularly monitored for signs of illness, and appropriate treatments are administered promptly.

- Genetics: The farm uses high-performing tilapia strains selected for rapid growth and feed efficiency.

The farm’s data shows that a consistent approach to these practices yields significant results. Over a production cycle, the farm records that for every 1.2 kg of feed given, the fish gain 1 kg of weight. This excellent FCR, combined with high survival rates and rapid growth, translates into higher profitability and sustainability. The farm’s success is a testament to the importance of a holistic approach to FCR management.

Fish Farm Struggling with Poor FCR and Improvement Strategies

In contrast, a shrimp farm in Vietnam experienced persistent challenges with poor FCR, averaging above 2.0. This resulted in increased feed costs and reduced profitability. The farm recognized the need for significant improvements and implemented a strategic plan.

- Diagnosis of the Problem: The farm conducted a thorough assessment to identify the root causes of the poor FCR. This included analyzing feed quality, evaluating feeding practices, assessing water quality, and examining fish health.

- Feed Optimization: The farm switched to a higher-quality shrimp feed with improved digestibility and a balanced nutrient profile. They worked with a feed supplier to customize the feed based on their specific needs.

- Feeding Practice Adjustments: The farm adjusted its feeding schedule, feeding frequency, and feeding methods. They implemented the use of feeding trays to monitor feed consumption and reduce feed waste.

- Water Quality Improvement: The farm invested in improved aeration and filtration systems. They implemented regular water changes and monitored water quality parameters more closely.

- Health Management Improvements: The farm improved its biosecurity protocols and implemented a more proactive health management program. They consulted with veterinarians and aquaculture specialists.

- Regular Monitoring: The farm started to closely monitor FCR, growth rates, and feed consumption on a regular basis. This allowed them to track their progress and make further adjustments as needed.

Following the implementation of these strategies, the shrimp farm observed a marked improvement in its FCR. Within one production cycle, the FCR decreased to approximately 1.7. This improvement was accompanied by increased shrimp growth and reduced feed costs, resulting in a significant boost in profitability. The farm’s experience underscores the importance of identifying and addressing the underlying causes of poor FCR and the positive impact of a targeted improvement plan.

Challenges and Solutions Related to FCR in Different Aquaculture Systems

FCR management presents unique challenges depending on the aquaculture system employed. For instance, in intensive recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS), maintaining optimal water quality and preventing disease outbreaks are critical for efficient FCR. In extensive pond aquaculture, factors like natural food availability and water quality fluctuations can significantly impact FCR.

- Intensive RAS: The primary challenge is maintaining consistent water quality, which directly affects feed intake and fish health. Solutions include advanced filtration systems, ozone or UV sterilization, and precise control of water parameters. Disease outbreaks can devastate FCR, so strict biosecurity and proactive health management are essential.

- Semi-Intensive Pond Aquaculture: In this system, the balance between natural food production and supplementary feeding is key. Overfeeding can lead to poor FCR and water quality degradation. Solutions involve careful monitoring of water quality, plankton blooms, and fish growth to optimize feeding rates.

- Extensive Pond Aquaculture: In extensive systems, the reliance on natural food sources means FCR can be variable. Supplementing with high-quality feed, particularly during periods of low natural food availability, can improve FCR. Monitoring water quality and fish health are still important.

- Cage Culture: Water flow and feed wastage are major concerns. Solutions include using high-quality, slow-sinking feed, and carefully monitoring feeding rates to minimize waste. Regular inspection and maintenance of cages are essential to prevent fish escapes.

The specific challenges and solutions are highly dependent on the species being farmed, the environmental conditions, and the management practices. Regardless of the system, a proactive and adaptive approach to FCR management is essential for success.

Key Takeaways from the Case Studies

The case studies highlight several crucial takeaways. Firstly, a holistic approach that considers all aspects of fish farming, from feed quality and feeding practices to water quality and health management, is vital for achieving excellent FCR values. Secondly, regular monitoring and data analysis are essential for identifying problems and tracking progress. Thirdly, there is no one-size-fits-all solution; the optimal approach to FCR management will vary depending on the specific aquaculture system, species, and environmental conditions.

Finally, continuous improvement is key. By consistently evaluating and refining their practices, aquaculturists can optimize FCR, improve profitability, and enhance the sustainability of their operations. The shrimp farm’s experience underscores the need for a proactive approach.

Final Wrap-Up

In conclusion, mastering how to calculate fish feed conversion rate is essential for responsible and profitable aquaculture. By understanding the factors influencing FCR, employing effective monitoring strategies, and continuously seeking improvements, fish farmers can unlock their operations’ full potential. Armed with the knowledge of FCR, FER, and PER, you’re now equipped to optimize your fish feeding strategies, enhance your farm’s efficiency, and contribute to a more sustainable aquaculture industry.

Remember, the journey to excellent FCR is an ongoing process of learning, adapting, and striving for excellence.