Understanding and preventing bloat in cattle is crucial for the health and productivity of your herd. Bloat, a potentially life-threatening condition, arises when excessive gas accumulates in the rumen, the first stomach compartment of a cow. This guide delves into the intricacies of bloat, offering practical strategies to safeguard your animals and ensure their well-being.

This comprehensive overview will explore the physiological mechanisms behind bloat, the various risk factors involved, and the different types of bloat that can affect cows. From dietary management and pasture techniques to water quality and emergency treatments, we’ll cover all aspects of prevention and response. Furthermore, we will also discuss the latest technological solutions to monitor rumen health and minimize bloat risk, ensuring you’re equipped with the knowledge to protect your cattle.

Understanding Bloat in Cattle

Bloat in cattle is a serious and often life-threatening condition characterized by an excessive accumulation of gas within the rumen, the largest compartment of a cow’s stomach. This buildup of gas can cause significant discomfort, impair breathing, and ultimately lead to death if not addressed promptly. Understanding the underlying physiological processes and recognizing the signs of bloat are crucial for effective prevention and treatment.

Physiological Processes Leading to Bloat

The rumen, a specialized fermentation vat, is home to a vast population of microorganisms that break down ingested feed. This process naturally produces gases, primarily methane and carbon dioxide. Normally, these gases are eliminated through eructation (belching) or absorption into the bloodstream. Bloat occurs when this normal gas elimination process is disrupted, leading to gas accumulation.

- Rumen Motility: Reduced rumen motility, caused by various factors such as dietary changes, stress, or certain diseases, can hinder the movement of rumen contents and the expulsion of gas.

- Gas Production Rate: Certain feeds, particularly lush, rapidly growing forages, can increase the rate of gas production in the rumen.

- Foam Formation: In frothy bloat, a stable foam forms within the rumen, trapping the gas and preventing eructation. This foam is often caused by specific plant compounds.

- Esophageal Obstruction: Rarely, physical obstructions in the esophagus can prevent gas from escaping.

Types of Bloat in Cattle

There are two primary types of bloat, each with distinct characteristics and causes:

- Frothy Bloat: This type is characterized by the formation of a stable foam in the rumen, preventing the cow from belching. It’s most commonly associated with the consumption of lush, rapidly growing legumes like alfalfa and clover, or certain grains. The foam is created by soluble proteins and other compounds present in these forages. The rumen becomes distended, and the cow struggles to breathe.

- Free Gas Bloat: In free gas bloat, gas accumulates in the rumen as a free layer above the rumen fluid. This type can be caused by a variety of factors that disrupt the normal eructation process. For example, a sudden change in diet or a blockage in the esophagus can lead to free gas bloat. The rumen distends, but the gas is not trapped in a foam.

Signs and Symptoms of Bloat in Cattle

Early recognition of bloat is essential for successful treatment. Observing the following signs and symptoms can help identify affected animals:

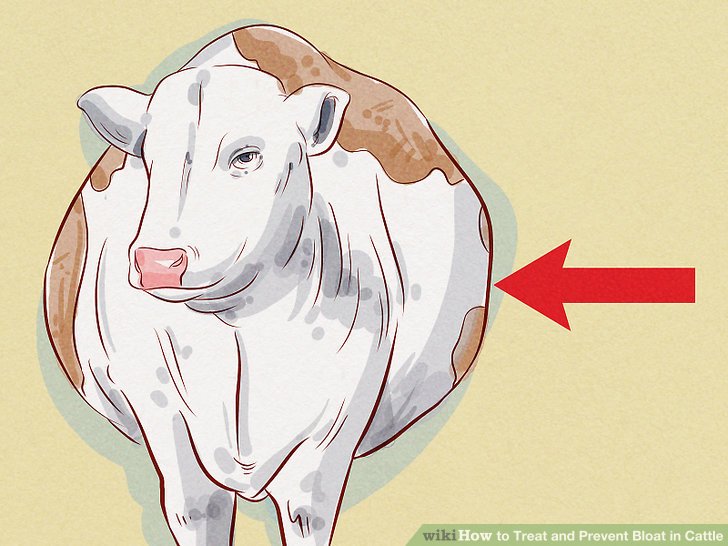

- Distended Abdomen: The most obvious sign is a pronounced swelling of the left flank, which may extend to the right flank in severe cases. The swelling often appears “drum-like” when tapped.

- Discomfort and Restlessness: Bloated cattle may show signs of discomfort, such as kicking at their abdomen, pacing, or lying down and getting up repeatedly.

- Labored Breathing: As the rumen expands, it can put pressure on the lungs, making it difficult for the cow to breathe. Breathing may become rapid and shallow, and the animal may extend its head and neck.

- Reduced Appetite: Affected animals often stop eating and may show a decreased interest in feed.

- Depression: In severe cases, the cow may become lethargic and depressed.

- Visual Cues: The left flank will visibly bulge. In free gas bloat, the distention may be more symmetrical. In frothy bloat, the distention often develops rapidly.

- Behavioral Changes: Affected animals may isolate themselves from the herd. They might exhibit signs of pain, such as teeth grinding or groaning.

- Sudden Death: If bloat is left untreated, the pressure on the diaphragm and lungs can eventually lead to respiratory failure and death.

Risk Factors and Causes

Understanding the factors that contribute to bloat in cattle is crucial for effective prevention and management. Bloat is a complex condition influenced by a combination of dietary, environmental, microbial, and management factors. Identifying and mitigating these risks can significantly reduce the incidence of bloat and protect the health and productivity of your herd.

Dietary Factors

Dietary choices play a significant role in the development of bloat. Certain forages and feeding practices increase the likelihood of this condition.

- Legumes: Legumes are a primary dietary factor. Rapid fermentation in the rumen and the production of stable foam are common with legumes. Alfalfa ( Medicago sativa), clover ( Trifolium spp.), and other legumes are frequently associated with bloat. These plants contain proteins that can stabilize the foam, preventing the eructation of gases.

- Concentrates: Diets high in rapidly fermentable carbohydrates, such as grains, can also contribute to bloat. The rapid fermentation of these carbohydrates leads to increased gas production in the rumen.

- Young, Lush Pasture: Immature forages, regardless of plant type, often have a higher protein content and lower fiber content. This combination promotes rapid fermentation and foam formation, increasing the risk of bloat.

- Feeding Practices: Sudden changes in diet or overfeeding of concentrates can disrupt rumen function and increase bloat risk. Introduce new feeds gradually to allow the rumen microbes to adapt.

Environmental Conditions

Environmental conditions can also significantly affect the risk of bloat in cattle. Weather patterns and other environmental factors influence forage growth and composition, impacting the likelihood of bloat.

- Weather Patterns: Bloat risk is often higher during periods of rapid forage growth, which are frequently associated with warm temperatures and ample rainfall. These conditions promote the growth of lush, protein-rich forages, increasing the risk.

- Dew and Frost: Dew and frost on pasture can exacerbate bloat risk. These conditions can affect the consistency and digestibility of forages, potentially contributing to foam formation.

- Temperature: While not a direct cause, temperature can influence forage composition. For example, warmer temperatures can encourage rapid growth in legumes, which are often associated with bloat.

Rumen Microbes

The rumen microbiome plays a critical role in the development of bloat. The balance and activity of rumen microbes directly influence gas production and the stability of rumen contents.

- Microbial Fermentation: Rumen microbes ferment feed, producing gases as a byproduct. The rate and type of fermentation, influenced by the composition of the feed and the microbial population, affect the amount of gas produced.

- Foam Formation: Certain rumen microbes can contribute to foam formation, which traps gas bubbles and prevents eructation. The presence of these foam-stabilizing microbes is a key factor in bloat development.

- Microbial Adaptation: The rumen microbiome can adapt to dietary changes. Sudden shifts in diet can disrupt the microbial balance, leading to increased gas production and bloat. Gradual dietary transitions help to maintain a stable microbial population.

Management Practices

Management practices significantly influence the risk of bloat. Grazing methods, supplementation strategies, and other management decisions can either increase or decrease the likelihood of bloat.

- Grazing Methods: The grazing method used impacts the risk of bloat. Continuous grazing on bloat-prone pastures can increase the risk because cattle have constant access to high-risk forages. Rotational grazing systems, where cattle are moved to fresh pastures regularly, can help mitigate the risk.

- Supplementation: Providing supplemental feed, such as ionophores or poloxalene, can reduce the risk of bloat. Ionophores alter the rumen microbial population to reduce gas production. Poloxalene is a surfactant that breaks down foam.

- Water Availability: Ensuring adequate water access is important for rumen function. Dehydration can disrupt the rumen environment and potentially increase bloat risk.

- Monitoring: Regular monitoring of cattle for signs of bloat is crucial. Early detection allows for prompt treatment and can prevent severe cases.

Dietary Management Strategies

Managing a cow’s diet is crucial for preventing bloat. This involves careful planning of what the cow eats, how it’s introduced, and the use of supplements when needed. A well-structured feeding plan can significantly reduce the risk of bloat and promote overall herd health.

Designing a Feeding Plan to Minimize Bloat Risk

Creating a feeding plan requires careful consideration of forage selection and introduction strategies. The goal is to provide a balanced diet that supports rumen health and minimizes the likelihood of bloat.

- Forage Selection: Choose forages that are less likely to cause bloat. Legumes, such as alfalfa and clover, are high-risk for bloat, particularly when lush and actively growing. Consider grass-based pastures, or a mixture of grasses and legumes, if legumes are used. Ensure the legume content does not exceed 50% of the pasture.

- Forage Introduction: Gradually introduce new forages to allow the rumen microbes to adapt. This slow transition helps prevent digestive upsets that can contribute to bloat. Start with small amounts of the new forage, increasing the proportion over several days or weeks.

- Supplementation: Provide supplemental roughage, such as hay or straw, particularly when grazing lush pastures. This helps stimulate rumination and saliva production, which can buffer the rumen and reduce the risk of bloat.

- Feeding Frequency: Offer feed frequently, rather than allowing cows to gorge themselves. This helps maintain a more stable rumen environment and reduces the risk of overeating and bloat.

- Water Access: Ensure cows have access to clean, fresh water at all times. Proper hydration is essential for healthy rumen function and digestion.

Introducing New Feeds Gradually

A gradual introduction of new feeds is essential for preventing digestive upset, including bloat. Abrupt changes in diet can disrupt the rumen microbial population, leading to gas buildup and potential bloat.

- Step-by-Step Introduction: Over a period of 7-14 days, gradually increase the proportion of the new feed while decreasing the proportion of the old feed. For example, if introducing a new concentrate, start by mixing a small amount of the new feed with the existing feed. Gradually increase the amount of the new feed each day while decreasing the amount of the old feed.

- Observation: Closely monitor the cows for signs of digestive upset, such as reduced feed intake, diarrhea, or changes in manure consistency. If any of these signs are observed, slow down the introduction of the new feed or temporarily revert to the previous diet.

- Adaptation Period: Allow the rumen microbes sufficient time to adapt to the new feed. This adaptation period is crucial for the efficient digestion of the new feed and the prevention of bloat.

- Hay as a Buffer: Providing hay alongside the new feed can help buffer the rumen and reduce the risk of bloat. Hay stimulates rumination and saliva production, which helps neutralize excess acid and maintain a healthy rumen environment.

- Individual Variation: Remember that individual cows may respond differently to dietary changes. Monitor individual animals closely and adjust the feeding plan as needed.

Comparing Different Bloat-Preventing Feed Additives

Several feed additives can help prevent bloat in cattle. These additives work through different mechanisms to reduce gas production or facilitate gas release.

| Additive | Mechanism of Action | Effectiveness | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poloxalene | Reduces surface tension in the rumen, allowing gas bubbles to coalesce and be eructated. | Highly effective when administered correctly. | Must be administered daily or as directed; available in various formulations (e.g., feed supplements, boluses). |

| Ionophores (e.g., Monensin, Lasalocid) | Alters the rumen microbial population, reducing the production of bloat-causing gases. | Effective in reducing bloat risk, especially in feedlot cattle. | Requires a withdrawal period before slaughter; can affect rumen fermentation and feed efficiency. Requires careful management to avoid toxicity. |

| Bloat Guard (e.g., certain surfactants) | Similar to poloxalene, reduces surface tension in the rumen. | Can be effective but may require more frequent administration than poloxalene. | Often administered through drinking water or feed; effectiveness can vary. |

| Vegetable Oils (e.g., Soybean Oil) | Can be added to feed to reduce foam formation in the rumen. | May be moderately effective in some cases. | Requires careful formulation and mixing; effectiveness can vary. Can potentially alter milk fat content. |

Proper Use of Anti-Bloat Supplements

Anti-bloat supplements are valuable tools in preventing bloat. However, they must be used correctly to be effective.

- Dosage and Administration: Follow the manufacturer’s instructions for dosage and administration. Dosage varies depending on the supplement and the size of the animal. Administer supplements regularly, especially when cattle are at high risk of bloat (e.g., grazing lush pastures). Poloxalene, for example, might be added to feed at a specific percentage, or given as a bolus, as per the label.

- Timing: Administer supplements before cattle graze high-risk pastures. This allows the supplement to be present in the rumen before the cows consume bloat-inducing forages.

- Delivery Methods: Supplements can be administered through various methods, including feed additives, mineral mixes, boluses, and water-soluble formulations. Choose the method that best suits your management practices and the specific supplement.

- Monitoring: Regularly monitor cattle for signs of bloat, even when using supplements. While supplements are effective, they are not foolproof. Observe the herd for any changes in behavior or signs of discomfort.

- Storage: Store supplements according to the manufacturer’s instructions to maintain their effectiveness. Improper storage can degrade the active ingredients and reduce the supplement’s efficacy.

Pasture Management Techniques

Effective pasture management is crucial in minimizing the risk of bloat in cattle. By carefully planning and implementing grazing strategies, producers can significantly reduce the likelihood of this potentially fatal condition. This section details various pasture management techniques that can be employed to create a safer and more productive grazing environment for cattle.

Managing Grazing for Bloat Reduction

Proper grazing management is a cornerstone of bloat prevention. This involves strategic manipulation of grazing practices to minimize the consumption of bloat-inducing forages.Rotational grazing is a key strategy. Instead of continuous grazing, where cattle have unlimited access to a pasture, rotational grazing involves dividing the pasture into smaller paddocks. Cattle graze one paddock for a limited time before being moved to another, allowing the grazed paddocks to rest and regrow.

This system offers several benefits:

- It prevents cattle from selectively grazing the most bloat-prone plants.

- It promotes more even forage utilization, leading to healthier pastures.

- It can reduce the overall intake of rapidly fermentable carbohydrates, a major contributor to bloat.

Grazing duration is also critical. Short grazing periods in bloat-prone pastures can limit the amount of risky forage consumed. Monitor cattle closely, especially during the initial grazing period, to observe any signs of bloat. It is advisable to introduce cattle to a new pasture gradually, allowing them to adapt to the forage. Providing access to dry hay or straw before turning cattle onto lush pastures can help buffer the rumen and reduce bloat risk.

Water Management and Hydration

Providing cattle with access to clean, fresh water is crucial for their overall health and is a significant factor in preventing bloat. Adequate hydration supports optimal rumen function and helps to minimize the risk of this potentially fatal condition. Proper water management is therefore an essential component of any bloat prevention strategy.

Importance of Clean Water

The quality of water available to cattle directly impacts their health and well-being. Contaminated water can lead to a variety of health problems, including bloat.

- Cleanliness: Water sources should be free from contaminants such as algae, bacteria, and chemical pollutants. Regular testing and maintenance are essential.

- Freshness: Stagnant water can harbor harmful organisms. Water troughs and tanks should be cleaned regularly to prevent the buildup of debris and promote freshness.

- Availability: Cattle should have constant access to water, particularly during hot weather or when consuming dry feed. Water intake is directly related to feed intake, and inadequate water can exacerbate bloat risks.

Potential Water Source Problems

Certain characteristics of water sources can increase the risk of bloat. Identifying and addressing these problems is a key part of effective bloat prevention.

- High Mineral Content: Water with excessive levels of certain minerals, such as sulfates, can disrupt rumen function and contribute to bloat. Water testing is essential to determine mineral levels.

- Algae Blooms: Algae blooms can contaminate water, releasing toxins that can negatively impact cattle health and rumen function. Monitoring and treating water sources for algae are crucial.

- Contamination: Water sources can become contaminated with various pollutants, including agricultural runoff, chemicals, and animal waste. These contaminants can disrupt rumen health and increase the risk of bloat. Proper fencing and water source management are critical.

- Temperature: Extremely cold water can reduce water intake, particularly during winter months, which could indirectly increase the risk of bloat. Ensuring water does not freeze is essential in colder climates.

Relationship Between Water Intake and Rumen Function

Water plays a vital role in rumen function, including digestion and the regulation of gas production. Adequate water intake is critical for maintaining a healthy rumen environment and preventing bloat.

- Rumen Hydration: The rumen requires a significant amount of water to function properly. Water is essential for microbial fermentation, which is the primary digestive process in the rumen.

- Digestive Processes: Water facilitates the movement of feed through the digestive tract and aids in the absorption of nutrients. Insufficient water can slow down digestion and potentially contribute to bloat.

- Gas Regulation: Water helps to regulate gas production in the rumen. Proper hydration supports the efficient removal of gases, reducing the risk of bloat.

- Example: In a study conducted by the University of California, Davis, it was observed that cattle with limited access to water showed a significantly higher incidence of bloat compared to those with unrestricted access. This highlights the importance of water intake.

Monitoring and Early Detection

Early detection of bloat is crucial for preventing severe cases and potential fatalities in cattle. Implementing a robust monitoring program allows producers to identify affected animals promptly, initiate timely treatment, and minimize losses. This proactive approach involves regular observation and the use of specific tools to assess cattle health and behavior.

Methods for Regular Monitoring

Regular monitoring for bloat involves a combination of visual observation, physical examination, and assessment of behavior. Implementing these methods consistently allows for early detection and intervention.

- Visual Observation: Observe cattle at least twice daily, ideally during feeding times and again later in the day. Look for signs of bloat, such as a distended left flank (the area between the last rib and the hip), a reluctance to move, and labored breathing. Note any changes in posture or gait. Pay close attention to animals that are separated from the herd or appear lethargic.

- Physical Examination: Conduct physical examinations on any animal suspected of having bloat. This includes palpating the left flank to assess the degree of distension and the presence of tympany (a drum-like sound). Monitor heart and respiratory rates.

- Behavioral Assessment: Observe cattle for changes in behavior, such as decreased appetite, reduced rumination (cud chewing), and signs of discomfort, like kicking at their abdomen or lying down more than usual. These behavioral changes can indicate early stages of bloat.

- Using a Rumenocentesis: In cases where diagnosis is uncertain, a veterinarian might perform a rumenocentesis. This involves inserting a needle into the rumen to collect fluid. The fluid’s characteristics can help differentiate between bloat and other conditions.

Checklist for Early Bloat Detection

Creating and consistently using a checklist facilitates the early detection of bloat. This checklist includes both physical examinations and behavioral observations.

- Physical Examination:

- Assess left flank distension: Grade the distension on a scale (e.g., 0-3, where 0 is normal and 3 is severe).

- Check for tympany: Gently tap the left flank and listen for a drum-like sound.

- Measure heart rate: Normal heart rate for cattle is typically between 60 and 80 beats per minute.

- Measure respiratory rate: Normal respiratory rate for cattle is typically between 20 and 40 breaths per minute.

- Behavioral Observations:

- Observe appetite: Is the animal eating normally?

- Assess rumination: Is the animal chewing its cud?

- Observe posture: Is the animal standing or lying down? Is it exhibiting signs of discomfort, such as arching its back or kicking at its belly?

- Note any changes in activity: Is the animal moving around normally, or is it isolated from the herd?

- Record Keeping:

- Document all observations, including dates, times, and findings.

- Note any treatments administered and the animal’s response.

- Maintain a record of bloat cases in the herd to identify potential risk factors.

Distinguishing Bloat from Other Digestive Issues

Accurately differentiating bloat from other digestive issues is critical for appropriate treatment. Various conditions can present with similar symptoms, requiring careful assessment.

- Vagal Indigestion: Vagal indigestion is a complex condition characterized by dysfunction of the vagus nerve, leading to various digestive disturbances, including rumen distension. Unlike bloat, which is characterized by rapid gas accumulation, vagal indigestion often involves fluid accumulation and slower onset. Distinguishing features include a “papple” shape (distension on both sides of the abdomen) and reduced gut motility.

- Hardware Disease: Hardware disease occurs when a sharp object, such as a piece of wire or metal, penetrates the reticulum, causing inflammation and peritonitis. Signs can include decreased appetite, reluctance to move, and a hunched posture. A key diagnostic tool is the use of a magnet to attract metallic objects.

- Acidosis: Acidosis is caused by an excessive intake of rapidly fermentable carbohydrates, leading to a drop in rumen pH. Symptoms include reduced appetite, diarrhea, and lethargy. Acidosis can sometimes cause rumen distension, but the character of the rumen contents (e.g., watery and acidic) differs from bloat.

- Other Causes of Abdominal Distension: Other conditions that can mimic bloat include intestinal obstruction, peritonitis, and tumors. A thorough physical examination and, if necessary, diagnostic tests such as rumen fluid analysis or ultrasound can help differentiate these conditions.

Emergency Treatment and Veterinary Care

Bloat in cattle can quickly become a life-threatening condition, necessitating prompt and appropriate intervention. Recognizing the signs of bloat and understanding the steps to take in an emergency can significantly improve a cow’s chances of survival. This section provides guidance on immediate actions, emergency treatments, veterinary care, and post-treatment recovery strategies.

Immediate Actions When Bloat is Suspected

When a cow exhibits signs of bloat, such as a distended left flank, labored breathing, and signs of discomfort, rapid assessment and action are crucial. Delaying treatment can worsen the condition and increase the risk of mortality.

- Assess the Severity: Observe the cow’s condition closely. Is the distension mild, moderate, or severe? Is the cow showing signs of distress like difficulty breathing, rapid heart rate, or a recumbent posture? The severity dictates the urgency of treatment.

- Remove from the Pasture: Immediately remove the affected cow from the pasture or feed source. This prevents further intake of the bloat-causing substances.

- Provide a Safe Environment: Move the cow to a shaded area with access to fresh water, if possible. Ensure the area is free of hazards that could cause further injury.

- Contact Veterinary Assistance: Simultaneously, contact a veterinarian immediately. Provide the veterinarian with details about the cow’s condition, including the observed symptoms and the suspected cause of the bloat. The veterinarian can provide guidance and arrange for a visit.

Procedure for Administering Emergency Treatments

Emergency treatments for bloat aim to relieve the gas pressure within the rumen. These treatments should only be administered by experienced individuals or under the direct guidance of a veterinarian. Incorrect application can lead to serious complications.

- Oral Administration of Anti-Foaming Agents: If the bloat is frothy, administer an anti-foaming agent orally. These agents break down the gas bubbles, allowing the cow to eructate (belch). Commonly used agents include poloxalene or vegetable oil. Follow the product’s instructions for dosage. For example, a typical dose of poloxalene is approximately 1-2 grams per 100 pounds of body weight.

- Use of a Stomach Tube: A stomach tube can be used to release gas if the bloat is not frothy or if anti-foaming agents are ineffective.

- Procedure: Carefully insert the lubricated stomach tube through the cow’s mouth and down the esophagus into the rumen. Gently rotate the tube as it is advanced.

- Gas Release: Once the tube is in the rumen, gas should begin to escape. If the tube is blocked by feed, gently flush it with water.

- Removal: After the gas is released and the cow appears more comfortable, slowly remove the tube.

- Use of a Trocar: A trocar is used as a last resort for severe cases of bloat where other methods have failed.

- Procedure: The veterinarian will use a trocar to puncture the rumen wall on the left side of the cow, in the area of greatest distension. The trocar allows for immediate release of the gas. This procedure carries risks, including peritonitis and infection.

- Post-Procedure Care: After the trocar is removed, the puncture site needs to be monitored for infection and treated as directed by the veterinarian.

When to Seek Veterinary Assistance and What to Expect

Veterinary assistance is essential in managing bloat, especially in severe cases. Early intervention by a veterinarian can significantly improve the prognosis.

- Severity of Bloat: If the bloat is severe, the cow is showing signs of distress, or the initial treatments are ineffective, immediate veterinary attention is necessary.

- Veterinary Examination: The veterinarian will conduct a thorough examination, which may include:

- Physical Examination: Assessment of the cow’s vital signs, including heart rate, respiratory rate, and body temperature.

- Rumen Auscultation: Listening to the rumen sounds to assess the degree of fermentation.

- Rectal Examination: Checking for other potential problems, such as impaction or displacement of the abomasum.

- Diagnostic Procedures: In some cases, the veterinarian may perform diagnostic procedures, such as rumen fluid analysis to determine the cause of the bloat.

- Treatment: The veterinarian will administer appropriate treatments, which may include anti-foaming agents, rumenotomy (surgical opening of the rumen), or other supportive care.

Post-Treatment Care and Recovery Strategies

After treatment for bloat, providing proper care and monitoring the cow’s recovery are crucial for a successful outcome. Recovery can take time, and careful management is necessary to prevent recurrence.

- Monitoring: Closely monitor the cow’s vital signs, appetite, and behavior. Watch for signs of complications, such as pneumonia, peritonitis, or rumenitis.

- Dietary Management: Gradually reintroduce feed to the cow. Start with small amounts of high-quality hay or a readily digestible feed. Avoid feeding large quantities of lush pasture or grains immediately after treatment.

- Water Access: Ensure the cow has access to fresh, clean water. Hydration is essential for recovery.

- Medication: Administer any medications prescribed by the veterinarian, such as antibiotics to prevent or treat infection.

- Prevention: Implement preventive measures to reduce the risk of future bloat episodes, as discussed in previous sections. This includes proper pasture management, dietary adjustments, and regular monitoring.

Breed and Individual Animal Considerations

Understanding the influence of breed and individual animal characteristics is crucial for effective bloat prevention. Certain breeds and individual animals are inherently more susceptible to bloat due to genetic predispositions, digestive physiology, and grazing behaviors. Recognizing these vulnerabilities allows for targeted management strategies to minimize the risk of bloat within a herd.

Breed Susceptibility to Bloat

Different cattle breeds exhibit varying levels of susceptibility to bloat. This variance is primarily attributed to differences in digestive tract anatomy, fermentation processes, and grazing habits. Breeds with a higher predisposition require more vigilant monitoring and proactive management practices.

- High-Risk Breeds: Breeds like the

-Hereford* and

-Angus* are often cited as being more susceptible to bloat, particularly when grazing on lush, rapidly growing pastures. Their digestive systems may not be as efficient at processing large volumes of easily fermentable feedstuffs. - Moderate-Risk Breeds:

-Dairy breeds*, such as

-Holstein-Friesians*, are also at an elevated risk, particularly during periods of high milk production when their feed intake is substantial. The rapid consumption of high-moisture feeds can exacerbate bloat risk. - Lower-Risk Breeds: Some breeds, such as

-Brahman*, are considered to have a lower inherent susceptibility to bloat. Their digestive physiology may be better adapted to handle fibrous or rapidly fermentable forages. However, even these breeds are not immune, and management practices must still prioritize bloat prevention.

Individual Cow Characteristics and Bloat Vulnerability

Individual cow characteristics can significantly influence bloat susceptibility. These characteristics, ranging from physical attributes to behavioral traits, can create a higher or lower risk profile for bloat within a herd.

- Age: Young calves and older cows may have a higher risk. Young calves may lack a fully developed rumen flora, making them more vulnerable to gas buildup. Older cows may have less efficient digestive systems.

- Body Condition Score: Cows in poor body condition, especially those with inadequate protein and energy intake, might be more prone to bloat. A compromised rumen function increases susceptibility.

- Feeding Habits: Cows that are aggressive eaters or tend to gorge themselves on feed are at a higher risk. This behavior can lead to the rapid intake of large quantities of fermentable material.

- Rumen Motility: Cows with reduced rumen motility are more likely to develop bloat. Impaired rumen contractions hinder the expulsion of gas, leading to its accumulation.

Impact of Genetics on Bloat Predisposition

Genetics play a significant role in determining an animal’s susceptibility to bloat. Breeding programs can be utilized to select for traits that reduce bloat risk, such as improved rumen function and grazing behavior.

- Heritability: Bloat susceptibility is heritable, meaning that the tendency to bloat can be passed down from parents to offspring. This makes genetic selection a viable strategy for bloat mitigation.

- Selection for Resistance: Breeders can identify and select animals with a lower incidence of bloat in their ancestry. This can be achieved through careful record-keeping, including information on bloat cases within the herd and family lineages.

- Breeding Strategies: Strategic breeding programs, involving the selection of sires and dams with desirable traits, can help to reduce the overall bloat risk within a herd. This proactive approach contributes to a healthier and more productive cattle population.

Technological Solutions

Modern technology offers innovative tools to enhance bloat management in cattle, providing farmers with real-time data and automated solutions to mitigate risks. These advancements can significantly improve animal health and productivity.

Monitoring Rumen Health with Boluses and Sensors

The utilization of boluses and sensors represents a significant stride in the proactive management of bloat. These devices, ingested by the cow, reside in the rumen and continuously monitor various physiological parameters.

- Rumen pH Monitoring: Sensors measure rumen pH, an essential indicator of digestive health. Deviations from the normal range (typically 5.5 to 6.5) can signal potential bloat risks. Real-time alerts allow for timely intervention, such as dietary adjustments.

- Rumen Contraction Monitoring: Some boluses track rumen contractions, providing insights into the efficiency of digestion. Reduced contraction frequency may indicate compromised rumen function, increasing the likelihood of bloat.

- Gas Production Detection: Certain advanced sensors can detect and quantify gas production within the rumen. Elevated gas levels, especially in the presence of specific feedstuffs, can trigger alerts for bloat risk.

- Data Transmission and Analysis: The data collected by these sensors is transmitted wirelessly to a central system, where it is analyzed. Farmers receive real-time alerts via mobile devices or computer dashboards, enabling immediate action.

Automated Feeding Systems to Reduce Bloat Risk

Automated feeding systems provide precision in dietary management, which is a key factor in bloat prevention. These systems offer a level of control that minimizes fluctuations in feed intake and composition.

- Precise Rationing: Automated systems deliver precisely measured feed portions, ensuring consistent intake and preventing overconsumption of bloat-inducing feeds. This is particularly important with lush pastures or rapidly fermentable concentrates.

- Controlled Feeding Frequency: Systems can be programmed to feed multiple times a day, promoting more consistent rumen fermentation and reducing the risk of large gas build-up. This can be especially beneficial for cattle grazing on high-risk pastures.

- Feed Composition Control: Automated systems allow for precise mixing of feed components, enabling farmers to carefully manage the ratio of roughage to concentrate, thus optimizing rumen health and reducing bloat potential.

- Real-time Monitoring and Adjustment: Some systems integrate with sensors to monitor feed intake and animal behavior, allowing for real-time adjustments to the feeding program based on individual animal needs and environmental conditions.

Applications of Precision Agriculture Techniques for Bloat Management

Precision agriculture, encompassing technologies like GPS, GIS, and remote sensing, provides powerful tools for optimizing pasture and feed management to minimize bloat risk.

- Pasture Mapping and Analysis: GPS-enabled systems can map pasture areas, identifying regions with high bloat potential, such as those with lush, rapidly growing legumes. GIS software can then be used to analyze soil conditions and plant species, informing grazing management decisions.

- Variable Rate Application (VRA) of Fertilizers: VRA technology allows for the targeted application of fertilizers, minimizing the over-fertilization of pastures and reducing the risk of excessive plant growth, which can increase bloat potential.

- Remote Sensing for Pasture Monitoring: Satellite imagery and drone-based sensors can monitor pasture biomass and vegetation health, providing early warning signs of high-risk conditions. This allows farmers to adjust grazing strategies proactively.

- Automated Weather Data Integration: Integrating weather data, such as temperature and rainfall, with pasture and animal health data allows farmers to anticipate bloat risks. For instance, warm, wet conditions can accelerate plant growth, increasing bloat potential. This integration aids in proactive management strategies.

Seasonal and Environmental Considerations

Understanding how seasonal changes and environmental conditions affect bloat risk is crucial for proactive cattle management. These factors significantly influence pasture composition, forage availability, and animal behavior, all of which contribute to the likelihood of bloat outbreaks. Effective management requires adapting strategies to mitigate these risks, ensuring the health and productivity of the herd throughout the year.

Seasonal Influence on Bloat Risk

Seasonal variations profoundly impact bloat incidence in cattle. The specific risks and management considerations vary depending on the time of year.

- Spring: This is often a high-risk period. The rapid growth of lush, immature forages, particularly legumes like alfalfa and clover, presents a significant bloat challenge. These plants contain high concentrations of soluble proteins and low fiber content, predisposing cattle to bloat. Early spring grazing, when forages are at their most succulent, requires careful monitoring and management.

- Summer: While the risk of bloat may decrease slightly compared to spring, it can still be present, especially if grazing on rapidly growing pastures after rainfall. Heat stress can also indirectly increase bloat risk by altering cattle’s grazing behavior and water intake. During drought periods, cattle may consume more dry, concentrated feed, which, if not properly managed, can lead to bloat.

- Autumn: Autumn can present a moderate risk. The composition of pastures changes, with some forages becoming more mature and fibrous. However, the regrowth of certain legumes after cutting or grazing can still pose a risk. Additionally, the accumulation of frost on pastures can damage plant cell walls, potentially increasing the release of bloat-causing substances.

- Winter: The risk of bloat is generally lower in winter due to the dormancy of many pasture plants and the reliance on stored feed. However, bloat can still occur if cattle are fed diets that are too high in rapidly fermentable carbohydrates or if they are introduced to new feeds without proper adaptation.

Weather Patterns and Bloat Outbreaks

Weather patterns are closely linked to bloat outbreaks. Understanding the relationship between weather and bloat can aid in predictive management.

- Rainfall: Heavy rainfall followed by rapid pasture growth creates ideal conditions for bloat. The lush, new growth is high in soluble proteins and low in fiber. This is particularly true for legumes.

- Temperature: Warm temperatures accelerate plant growth, increasing the risk. Heat stress can also lead to altered grazing behavior and water intake, potentially increasing the risk.

- Frost: Frost can damage plant cell walls, leading to the release of intracellular contents and potentially increasing the risk of bloat. Grazing frosted pastures can be especially dangerous.

- Humidity: High humidity can contribute to the growth of bloat-causing bacteria in the rumen.

- Wind: Strong winds can dry out pastures, which might indirectly affect bloat risk by changing the palatability and composition of forages.

Adapting Management Strategies

Effective bloat management requires adjusting practices based on seasonal and environmental conditions. Proactive adaptation is essential for mitigating risks.

- Pasture Management:

- Spring: Delay grazing on high-risk pastures until plants have matured slightly. Use rotational grazing to allow forages to develop more fiber. Consider strip grazing or limit grazing on legumes.

- Summer: Monitor pasture conditions and adjust grazing accordingly. Provide access to dry hay or other roughage to balance the diet. Ensure adequate water availability.

- Autumn: Monitor for regrowth of legumes and adjust grazing strategies. Consider using bloat-preventing supplements if necessary.

- Winter: Ensure a balanced diet with adequate fiber. Monitor for any changes in feed that might increase bloat risk.

- Dietary Adjustments:

- Spring: Supplement with dry hay or other roughage before turning cattle out onto high-risk pastures. Use bloat-preventing supplements like poloxalene or ionophores as directed by a veterinarian.

- Summer: Provide access to a balanced diet, considering the pasture conditions. Adjust the amount of concentrate feed to avoid rapid fermentation.

- Autumn: Monitor the diet composition and adjust as needed. Supplement with roughage if pasture quality declines.

- Winter: Ensure a balanced diet with adequate fiber. Avoid sudden changes in feed.

- Monitoring and Early Detection:

- Year-Round: Regularly monitor cattle for signs of bloat, such as distended left flank, discomfort, and reduced appetite. Early detection is critical for timely intervention.

- Seasonal Adjustment: Increase the frequency of monitoring during high-risk periods like spring and periods of rapid pasture growth.

- Water Management:

- Year-Round: Ensure a constant supply of fresh, clean water. This is especially important during periods of heat stress or when cattle are consuming dry feed.

End of Discussion

In conclusion, effectively preventing bloat in cows requires a multi-faceted approach, encompassing careful dietary planning, diligent pasture management, and proactive monitoring. By understanding the causes, recognizing the signs, and implementing the strategies Artikeld in this guide, you can significantly reduce the risk of bloat, promoting the health and prosperity of your cattle operation. Remember, vigilance and informed action are your most powerful tools in safeguarding your herd from this serious condition.